Milwaukeeans Inspired by Steinbeck’s Social Message

Milwaukee-born actor and educator Paul McComas performed from John Steinbeck's work at Marquette, and local activists testified to the novelist's impact.

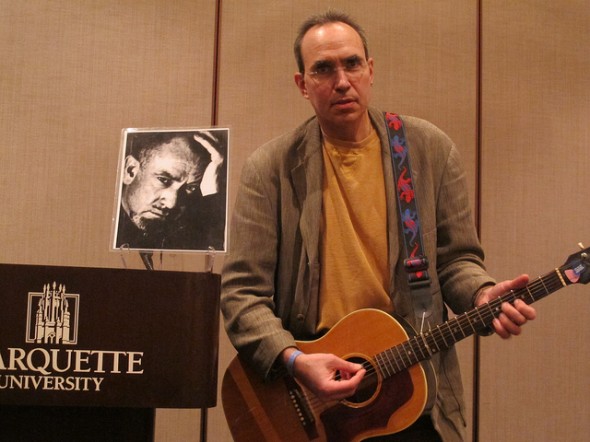

Author-Actor-Educator Paul McComas performs Bruce Springsteen’s stirring “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” inspired by “The Grapes of Wrath.” To his right is a photo of John Steinbeck. (Photo by Jennifer Reinke)

Last year marked the 75th anniversary of John Steinbeck’s classic “Of Mice and Men,” and it’s been more than 50 years since the author passed through Wisconsin on the road trip he chronicled in “Travels with Charley: In Search of America.” Nonetheless, author-actor-educator Paul McComas believes that the relevance of Steinbeck’s message to local social justice issues is as timely as ever.

Through dramatic readings from the aforementioned works, as well as from “The Grapes of Wrath,” “Cannery Row” and “East of Eden,” McComas provided an overview of Steinbeck’s career, which was bookended by two periods of social unrest: the Great Depression and the civil rights movement. McComas also performed Bruce Springsteen’s “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” inspired by “The Grapes of Wrath.”

The center invited McComas to perform because he engages and challenges audiences to think about themes central to peacemaking through the humanities, said Associate Director Patrick Kennelly.

“Peacemaking is transforming structures and relationships to provide for everyone’s well-being,” he said. “Through this presentation Paul engages the audience to think about how Steinbeck responded to social indignity and along the way invites us to reflect on how we respond to (it).”

Margaret Swedish, director of the Spirituality and Ecological Hope project of the Center for New Creation, reflected on the relevance of Steinbeck’s social message to her career in social activism. (Photo by Jennifer Reinke)

Steinbeck did just that for Margaret Swedish when she was a middle school student, she said. Now director of the Spirituality and Ecological Hope project of the Center for New Creation, Swedish recalled early encounters with Steinbeck’s “haunting” vision of poor and working-class characters such as the Joad family in “The Grapes of Wrath” and the workers of Cannery Row.

“It was very vivid and it was a world that, growing up in the suburbs of Wauwatosa, I didn’t know and had no way to see,” Swedish said. “I think we still live in a culture where affluent people have no idea what’s going on in the lives of poor, struggling people. The importance of Steinbeck is to give us a vivid, compelling portrait of the lives of those people – to humanize them for us,” she said.

Swedish, who lives in Bay View, is a social and environmental activist, writer and speaker. She was particularly moved by Steinbeck’s model of solidarity with poor and oppressed peoples by “witnessing to the truth of their situation, and seeing it through the lens of social justice and human dignity…making the poverty and suffering visible in a way that sears the conscience.” This approach, she said, “was the heart of (the) Central America solidarity work” she did for a quarter century.

And, for “poor, struggling people,” Swedish said, “Steinbeck gives them an incredibly dignified image of themselves.”

This is how Billy Malloy, a Marquette University alum and registered nurse at the Wheaton Franciscan St. Joseph Campus, related to Steinbeck. As a student, Malloy volunteered and lived at the Casa Maria Hospitality House, part of the Catholic Worker Movement which aims to realize Christian gospel values through political activism and service to those on the margins of society. Malloy said the Avenues West neighborhood in which Casa Maria is located often received a bad rap from his peers for being unsafe and impoverished.

He found, however, “It’s not always true, and even in some of those less developed neighborhoods there’s community.” Of Avenues West, he said, “The whole neighborhood is a wonderful community and it’s unexpected.”

Added Malloy, “Steinbeck was good at finding those communities in places people didn’t look.” The communities help people to define and place themselves, he said. “So even in places that are relatively disadvantaged, people by working together can make them beautiful and nice to live in – good neighborhoods.”

Rose Herriges stands in front of a wall hanging that McComas pointed out during his presentation. It reads, “Love is found in deeds more than words.” (Photo by Jennifer Reinke)

Rose Herriges, a Whitefish Bay resident and assistant buyer for The Bon-Ton Stores, Inc., said she was “surprised in a good way” by McComas’ emphasis on Steinbeck’s social message. She said she attended because “The Grapes of Wrath” is one of her favorite movies and she has read several of Steinbeck’s books. “I had no idea that the Center for Peacemaking was behind this,” she said.

Herriges appreciated the parallels between Steinbeck’s political activism and recent issues in Wisconsin politics that McComas highlighted. Steinbeck staunchly opposed Republican U.S. Sen. Joe McCarthy of Wisconsin and the House Un-American Activities Committee for their far-reaching anti-Communist regulations and actions which, according to McComas, “fomented an atmosphere of paranoia and distrust.”

In a 1957 essay published in Esquire, Steinbeck defended playwright Arthur Miller, who was on trial for Communist conspiracy. He wrote, “A law which is immoral does not survive and a government which condones or fosters immorality is truly in a clear and present danger.”

McComas said Steinbeck’s resistance to McCarthyism is “as close as we could get to (his) rebuttal of (the Gov. Scott) Walker regime and its attack on unions.” Steinbeck was a great proponent of organizing, he said.

Bringing it back to present-day Milwaukee, Herriges said, “Pushing aside the labor unions…hurts a lot of people, especially…because we’re a middle-class kind of city and we still have some manufacturing here and people in those kinds of jobs are being dismissed.”

Attendee Louise Cainkar, Marquette University associate professor of sociology and social welfare, said, “Steinbeck dealt with social inequalities, and…the fact that Milwaukee…has neighborhoods that vary widely in housing quality, personal safety and access to healthy food is a symptom of social inequality. If our society had a different approach to human life and human dignity, where it would be assumed that certain fundamentals of life should be of good quality for everyone, then these neighborhood issues would be much less severe.”

While Steinbeck’s fiction writing isn’t generally political, McComas said, the solutions to social problems he posits can be extrapolated into public policies.

“He understood that the personal is political and the political is personal,” McComas said. “In his fiction, he simply tells stories and through his characters political contents invariably come to the surface.”

According to C.J. Hribal, author and English professor at Marquette University, “Steinbeck reminds us through his fiction that the lives of people at the bottom of the social-economic ladder – almost always there through no fault of their own – matter, that their fates matter, that community matters, that we have a responsibility to each other.”

This story was originally published by Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, where you can find other stories reporting on fifteen city neighborhoods in Milwaukee.