Track back

Inova/Kenilworth Gallery

2155 N. Prospect Avenue

Adelheid Mers & Indexical Frontiers

Now – May 11, 2008

I almost decided not to review the new Inova/Kenilworth exhibition (now – May 11, 2008). The lengthy press release was exhausting, and I was somewhat confused by the information surrounding Chicago-based artist Adelheid Mers. According to the press release, her “Organogram,” a mapping of the people, positions, procedures, foundations and economic conditions that make up a functioning university arts program (specifically the Peck School of the Arts), produces not a critique, but a projection. But it also claims that the Organogram “reveals the artist’s bias as she gives shape to a visual report of what she has observed.” I had to ask myself, if the work “reveals a bias,” how then can it not be a critique? Of course, perhaps the artist was protecting herself from possibly offending the Peck School, which commissioned the project.

I almost decided not to review the new Inova/Kenilworth exhibition (now – May 11, 2008). The lengthy press release was exhausting, and I was somewhat confused by the information surrounding Chicago-based artist Adelheid Mers. According to the press release, her “Organogram,” a mapping of the people, positions, procedures, foundations and economic conditions that make up a functioning university arts program (specifically the Peck School of the Arts), produces not a critique, but a projection. But it also claims that the Organogram “reveals the artist’s bias as she gives shape to a visual report of what she has observed.” I had to ask myself, if the work “reveals a bias,” how then can it not be a critique? Of course, perhaps the artist was protecting herself from possibly offending the Peck School, which commissioned the project.

The exhibition, curated by Nicholas Frank, also includes the work of Michael Banicki, Annabel Daou and Renato Umali, all participating in Indexical Frontiers.

I visited the Kenilworth Building shortly after the March 28 opening. The alleged point of Mers’ project and process is to help people find “new ways of thinking about their institutions.” Eight questions were included in an online survey, with the anonymous replies to be no more than 2,000 words. Those wishing to schedule an interview with the artist were asked to provide an email address. The gallery-sitter that day was a 23-year-old pursuing an Arts Education degree with a double major in painting and drawing. She told me her favorite works in the exhibition were Umali’s, who earned his Master of Fine Arts if Film and Video Performance from UW-Milwaukee and presently teaches in their Film Department. I agree with the young woman.

His repertoire is a meticulously crafted presentation of personal data he’s recorded over an eight-year span. You might say this slice of his life is one big spreadsheet – with a twist. Umali has good days and bad days and in-between days, and you can locate his ups and downs by studying his richly detailed, colorfully designed graphs. A bad day is a black day. When his mood lightens, the squares morph to sunny shades of yellow. It’s all very prim and proper in the way that math is prim and proper; it’s easy to imagine Umali as a busy accountant, ticking off his life’s moments and making sure that everything balances. He maintains a piano studio for private instruction somewhere in the Kenilworth building, likely with not one but two metronomes. The gallery-sitter/art student remarked that Umali’s work “is something I would never have thought of.”

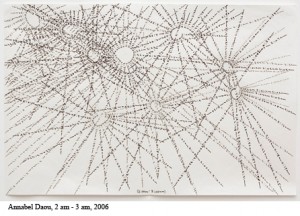

Across from Umali’s offerings is a wall of obsessive notations on white paper, so tiny and fragile-looking that I feared they might disappear from sight. Born and raised in Beirut, the artist, Annabel Daou, moved to New York in 1999, which may explain why her feathery notations seem to cling to the paper, as if they didn’t want to leave too large a footprint.

Michael Banicki’s six large (48” x 48”) paintings occupy much of the south wall. This painter is stuck in the look-at-me mud of the ‘70s. A nearby information sheet implies he’s been collecting stuff forever, from gumball machine charms and marbles to coins and baseball cards, etc. His paintings (in candy colors applied with messy, unfinished edges) deal with impressions of small towns, some familiar, some not, each depicted by a rah-rah banner. On the opposite wall are his color Xerox lists (“6,140 Favorite Towns”). It drove me nuts. The sheer amount of time the artist spent on the almost endless list was time wasted, mine and his, though I did valiantly try to tie the list in with some of the names on the nearby paintings. Either I was confused or the artist gave up on proper tracking. It could have been his way of telling us to distrust all information, but the sum of his efforts failed to move me.

Michael Banicki’s six large (48” x 48”) paintings occupy much of the south wall. This painter is stuck in the look-at-me mud of the ‘70s. A nearby information sheet implies he’s been collecting stuff forever, from gumball machine charms and marbles to coins and baseball cards, etc. His paintings (in candy colors applied with messy, unfinished edges) deal with impressions of small towns, some familiar, some not, each depicted by a rah-rah banner. On the opposite wall are his color Xerox lists (“6,140 Favorite Towns”). It drove me nuts. The sheer amount of time the artist spent on the almost endless list was time wasted, mine and his, though I did valiantly try to tie the list in with some of the names on the nearby paintings. Either I was confused or the artist gave up on proper tracking. It could have been his way of telling us to distrust all information, but the sum of his efforts failed to move me.

It was with strained eyes and frayed nerves that I arrived at Adelheid Mers “An Organogram of the Peck School of the Arts.” The artist spent days interviewing persons in and around the school, and along the way she incorporated an online survey. An Associate Professor at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, she teaches in the Arts Administration and Policy program.

Her central work, which takes up most of an interior wall, is big and easy to read, but unless you are an “insider” or privy to the results of her survey, it is difficult to decipher. From the standpoint of composition and color, it is, as the press release touts, “whimsical,” which to my mind is a catch-all word signifying nothing much. The scattering of images of African animals (elephants, giraffes) suggest that art school is a jungle. Yes, I got it when she included a yellow-green sofa in the lower right-hand corner of the work, a sofa labeled “curator,” “director,” and so forth, but it came off as coy rather than thoughtful. A nearby piece, interesting for its rawness, depicts gears within a large wheel, raising the possibility that should a few gear-teeth break loose, all would go awry within the “art school wheel.” Her take on Utopia and Utopian places (including the Amana Colonies in Iowa – currently a Utopia for tourists) is balanced with lists of Dystopias. In between is the safe ground most of us occupy – the space, I would venture to say, occupied by most of the 2,000 students at the Peck School of the Arts who grind on in hopes of finding their place in the world.

I’m not sure what the point of the drawing-bench design competition is, other than to include students who produced apathetic, half-baked drawings of possible improvements on the wretched wooden benches that students of drawing are forced to endure. A few had “honorable mention” tags, but there seemed to be no winner on the day I visited. “Stallion,” an intricate and fun design resembling a cartoon execution chamber, was by far the best of the grouping. Almost all of the designs included cup holders (and some incorporated padded seats!) – though I fail to see what cup holders have to do with the discipline of drawing. It would have been swell to have a genuine butt-breaking drawing-horse nearby, if only as a reminder that change can start at (or with) the bottom. The gallery-sitter said she’d like improved equipment and more display areas for student work, “as long as it doesn’t cost too much.” She participated in the online survey, and that was her answer to query # 6.

On July 1, Wade Hobgood will become the new dean of the Peck. His aim is to build partnerships between the venue and the community, which basically means raising money to keep the school viable. It’s reasonable to assume Mr. Hobgood, currently a professor of Mass Communications at the University of North Carolina-Asheville, has a grip on how to communicate effectively, but I am concerned that Inova galleries will become a marketing tool focused solely on “selling the school” rather than bringing viewers the best of the interdisciplinary arts. These goals are not necessarily at opposite poles, but it will be tricky meshing the gears to everyone’s benefit. Time will tell.

I do yearn, though, for more of the great art that opened the splendid Inova/Kenilworth space in 2007. Scrawled messages, rambling narratives tacked to walls, draped fabrics and endless charts of self referential meanderings leave me wondering if today’s uber-hip artists are intent on spinning cocoons around themselves, and to hell with those of us who are intent on connecting — if not entirely, then at least in part.

On a spectacular spring day, a week following my initial visit, I stopped in for a second look. A further study of Annabel Daou’s six ink-on-paper drawings (minute-by-minute compilations of 24 hours passing in time) made it clear that her works succeed both as art and as time-trackers. Nearby is a small white pedestal with a delicate carved screen insert. It’s the work of Amy Byrum and her sister, Greta, who designed the sound-scape. Atop the pedestal is Daou’s elegant 120-page miniature, a book of hours 2006.

On a spectacular spring day, a week following my initial visit, I stopped in for a second look. A further study of Annabel Daou’s six ink-on-paper drawings (minute-by-minute compilations of 24 hours passing in time) made it clear that her works succeed both as art and as time-trackers. Nearby is a small white pedestal with a delicate carved screen insert. It’s the work of Amy Byrum and her sister, Greta, who designed the sound-scape. Atop the pedestal is Daou’s elegant 120-page miniature, a book of hours 2006.

Someone had left a message on the vinyl sheet requesting comments or suggestions for future collaborations. A week earlier, I scrawled a message suggesting they bring a lecturer from a “Utopia,” and the commenter replied thusly: “Black Rock City, aka. Burning Man, is a Utopia, but only exists one week per year.”

Of course the best of all possible worlds for Inova/Kenilworth is to raise enough money to bring it to full fruition. I asked curator Frank about his budget and he encouraged me to interview UWM employees, Polly Morris and Bruce Knackert. I’ll do my best to keep you informed on what it will take to mesh those problematical gears. Time will tell. VS