The line forms here

The line: the beginning of possibilities, the basis of all art, begins at Inova/Kenilworth in an adventurous and well-balanced exhibit, which I reviewed in two prior features this week (Read part one and part two). If this prelude to spring forecasts what’s on the Kenilworth horizon, those who moan about our “dismal” art scene are perhaps looking in all the wrong places.

It wasn’t too long ago that if you yearned to view art, the choices were narrow: museums and a few privately owned galleries, plus exhibitions at universities. Now that we have a tide of technology, a tsunami of art experience is readily available via the internet. Locals can peruse Susceptible to Images, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel art critic Mary Louise Schumacher’s varied offerings, MKE, OnMilwaukee and any number of blogs and logs encouraging virtual space wanderers. There are seductive sites with excellent hi-res images and mountains of information, so why leave your cave when you can tour plopped in front of a computer, maybe with some wine and cheese? Parking space abounds, and you can Google and YouTube forever in your underwear. In effect, your home becomes your gallery, devoid of overzealous gallerists rushing forth to gush, “Isn’t this gorgeous!”

During my third and final visit, I duly noted that 160 souls attended the opening reception, and I spoke at length with a 21-year-old UWM senior, Nicholas Teeple. He just started as a “gallery guard” and is enrolled in DIVAS, the university’s digital imaging, video, animation and sound program.

He hasn’t taken any courses in drawing, and remarked that the computer “doesn’t lend itself to drawing and perhaps makes it less relevant, I guess.” I asked him how he intended to use a degree from a program he believes is challenging, rewarding and “full of potential.” He is particularly interested in time-based media, in the “blossoming” video and mash-up culture, and down the road may get into performance and installation art.

We talked about the anxiety/paranoia content of the exhibition. “By the way,” he asked, “just who are you writing this for?” For a moment, I thought maybe he was paranoid. “Fear-mongering is just another form of control,” he said as we discussed the show’s overall theme. “It’s a form of control embraced by the media.”

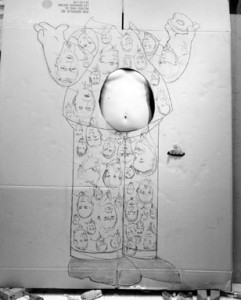

Claire Pentecost, one of the two artists I was there to review, has 14 pieces in the exhibition, ranging in size from 64” x 52” unframed giclee prints to framed 10”x 8” palladium prints. She teaches drawing, critical theory and interdisciplinary seminars and the School of the Art Institute in Chicago and refers to her photographs as “extracted;” the initial images were drawn on the walls of a derelict apartment she rented as a studio. Additional layers evolve via 8”x10” negatives, which morph to giclee or palladium prints. At first glance I was distracted by the decision to intermix the smaller palladium prints with the large, glossy giclee prints. The former, with their elegant air of antiquity, looked overpowered by their big, theatrical neighbors.

Claire Pentecost, one of the two artists I was there to review, has 14 pieces in the exhibition, ranging in size from 64” x 52” unframed giclee prints to framed 10”x 8” palladium prints. She teaches drawing, critical theory and interdisciplinary seminars and the School of the Art Institute in Chicago and refers to her photographs as “extracted;” the initial images were drawn on the walls of a derelict apartment she rented as a studio. Additional layers evolve via 8”x10” negatives, which morph to giclee or palladium prints. At first glance I was distracted by the decision to intermix the smaller palladium prints with the large, glossy giclee prints. The former, with their elegant air of antiquity, looked overpowered by their big, theatrical neighbors.

But I decided that the decision to intermix sizes was correct because it sets up a contrast between the brainy (and strangely Victorian) past and the crush of private interests that drive commercialization. She has this to say about the role of fine art in our current culture:

“Any works that seeks to overcome the quite successful marginalization of the fine arts must occupy multiple distribution streams, i.e., publications, websites and discussion threads, public lectures and discussions, especially if we want to do more than comment on a corrupt system. The more compelling challenge seems to propose different ways of being creative …”

Pentecost cites technology, the human survival adaptation, as having its roots in the hand. “I’m interested in the instability of the categories we use to separate the body and technology,” she writes on her website. For this artist, the big question continues to be “What kind of world do we want to live in?” Through her art, an intelligent exploration of the many modes of “drawing,” she seeks the answer, and in doing so seems to have found the kind of world she wants to live in.

|

| Robyn O’Neil. The Beginning, 2007. Graphite on paper. |

Robyn O’Neil, a native of Omaha who currently lives and works in Houston, participated in the 2004 Whitney Biennial and is represented by a single graphite drawing (“The Beginning 2007”) hung on the north wall in what Curator Frank describes as a “cathedral space.” Perfectly placed and framed in stark white, the initial effect is one of water, land and sky neatly divided. Are those birds flying through the atmosphere? Come closer: they are Homo sapiens (tiny and intricately expressed), but are they falling from above, cast asunder like fallen angels, or are they being sucked skyward into a kinder – or a more hellish – realm? It could be they are biding time in purgatory, where all is undecided. The graphite air, tense with expectation, is not so heavy as to drown the 66” x 66” paper with sodden imagery, and O’Neil’s touch leaves room (the room of negative space, the point of excellent drawing) for considering the human condition, past, present, and future — assuming there is a future.

Much credit for this seamless exhibition goes not only to the participating artists, but also to the careful planning by the dynamic duo, Curator Nicholas Frank and Director of Galleries, Bruce Knackert. The show runs through March 25 at Inova/Kenilworth, 2155 N. Propsect Avenue, part of the Institute of Visual Arts at the Peck School of the Arts at UWM. We encourage you to step away from your screen and pay the exhibition a visit. VS