Further Considerations

In part one of my look at the Inova/Kenilworth exhibition (now – March 14), I signed off with a few questions for the exhibit’s curator, Nicholas Frank. Because there has been controversy about the balance of men vs. women receiving Mary L. Nohl Fellowships, and because the current Inova/Kenilworth event features four women and one man, I thought this might be his way of smoothing things out.

Here’s his reply:

My programming isn’t a direct response to the Nohl Fellowship situation, because the problem is not with the Nohl program; it exists in the art world at large. I don’t think it’s difficult to program excellent exhibitions that reflect the actual gender balance among practicing artists.

He continued his comments with some thoughts on shaping shows:

I curate to reflect what artists are doing. The shows need to be relevant to the general art-going public, and also to the university audience, because we want Inova to be a curricular resource within the Peck School of the Arts. The drawing show illustrates the rise of drawing and narrative strategies among contemporary artists, and is useful for visual art faculty and students in that it expands notions of what drawing is and can be. There are sculptural, photographic and conceptual elements at play in this show, too.

As Frank noted in his statement, the show includes “sculptural, photographic, and conceptual elements.” As a unit, the entire exhibit is provocative, but not over-the-top, and from my standpoint the drawing theme holds true while conveying social anxieties. This is no easy trick, for how does a fine artist use words like “flatulence” and “poop” (and other arguably vulgar words) in a way that makes you want to keep reading? Deb Sokolow does it via story-telling. Her choice is freedom of expression; she almost dares you to hang in there, to see if the text and images (attached to several walls with push pins and tape) will lead you to a satisfactory end. But don’t expect her tale to necessarily end well. Unless you are a true fan of the wild, it takes time to explore her work (she’s a fan of Nancy Drew books and has included an image of Nancy in her narrative). The tale’s characters are fraught with neuroses – fellow employees who are back-stabbers, a bookstore drug dealer who deals from his office. As a former bookstore employee, she should know. When Sokolow was installing her work, she told me she was worried that maybe she hadn’t spelled all the words correctly. Her comment was hilarious, but actually, I think her comment is part of her personal neurosis. The installation will be seen by some viewers as slapdash, but it struck me as slap-happy, the exact opposite of what age-old notions tell us drawing “should be.” She’s no Rembrandt, but then again, Nancy Drew was no Sherlock Holmes. I found myself thinking of the Chicago outsider artist Henry Darger when I looked at her piece, aptly titled “The Trouble with People You Don’t Know.” I don’t know Sokolow, but I had no trouble liking her work.

|

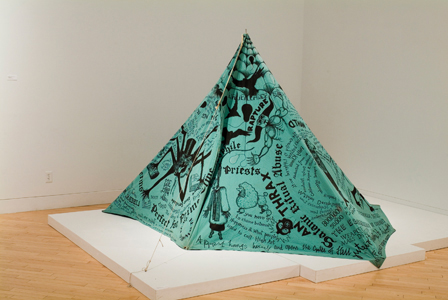

| Dominic McGill. Orchestra of Fear, 2005. Ink on tent canvas |

Dominic McGill is the artist whose tent came packed in a box, along with crunchy autumn leaves. Unpacked, it is quite a sight. Tents bring to mind good times from my past: camping and sleep-outs and creep-outs in my childhood backyard. McGill’s tent (an original Boy Scout canvas model purchased on eBay and anchored to the gallery’s concrete floor) is certainly creepy. It appears to be dyed, and the green hue suggests something is rotten in Denmark. The exterior of the entire pyramid-shaped work is covered with statements and images: “Ethel & Julius Rosenberg Executed,” “Pedophile Priests” (accompanied by a gruesome drawing of a bug-eye priest hanging from a rope), “In the ‘70s & ‘80s Post-Roe V. Wade,” “Thomas Hamilton, Ex-Scoutmaster, Kills 16 Children, 1 Teacher + Self.” I spent quite a bit of time walking around, standing back from, and peeking into the tent’s entry flap which was left slightly open. The interior was dark, and depending on your mindset, it was either a shelter from a nasty world, or a shelter for the nasty. At the top of the tent, a black vulture looms near a web of words, including “Surveillance Society.” In our high-tech culture, who among us is being watched? Are we the surveyors or the surveyed? Is there any place free of anxiety? Hunkered down in a tent somewhere on the edge of the world, with no means of communication … is total solitude the ultimate refuge, the only answer?

Near McGill’s tent from hell, Amy Ruffo’s drawings epitomize what most folks think of when they think of drawing: the artist, the pencil, the paper. Her whispering landscape is barely there and consists of eloquent lines in a volume of white. Ruffo grew up in Nebraska, and her approach to her materials is strict the way that the land of Nebraska is strict. She seems to be taking a journey in this disciplined work, traveling westward to where a mountain looms, crosshatched. The artist’s eye, the brain, the hand, the blank space resists the anxious urge to fill each nook and cranny. There’s so much unforgiving white; so much light. Don’t whip by this piece (another of her drawings is just around the corner) or blow it off because there are no mysteries to be solved, no political statements to be unsnarled, no artful tricks to unearth. Curator Frank says it best in the essay (“Fill in the Blanks”) that accompanies the exhibition:

The best drawing activates the blank ground of the paper, warping, bending and fitting it with space and volume. How that blank space is used, how it is left alone, is what allows the viewer’s imagination to make of a flat plane a boundless, timeless space charged with emotion and meaning …

Part three of this series of coverage of the Inova exhibition, specifically the works of Claire Pentecost and Robyn O’Neil, will be with you soon.

Gallery hours are Wednesday-Sunday, noon – 5pm & Thursdays until 8pm. Be advised there is limited parking in the area, but the building has free public parking on the Farwell (west) side. More information available at Inova’s website.