How Wisconsin Invented Public Radio

In 1917 Wisconsin Public Radio began, becoming a model for NPR, others. Excerpt from a book.

Science Hall, where Earle Terry and his students built 9XM. The Chemical Laboratory (600 N. Park) to the right provided the first home for WHA-TV in 1954. WHi Image ID 58314

No one knows the exact date, but it happened during the first three months of 1917. Physics department assistant professor Earle Terry and his wife, Sadie, invited a group of faculty, deans, and friends to their home to hear the “first broadcast” of the University of Wisconsin radio station. For several years, Professor Terry and his students had been transmitting the dots and dashes of Morse code. Only the geeks of the day who shared their interest in radio technology could decipher it, but this night would open the transmission to all who listened. In Terry’s Science Hall lab, graduate student Malcolm Hanson had rigged a telephone mouthpiece to capture the sound from the horn of a phonograph. When his guests gathered, Terry called Hanson and said, “We are all ready.” Hanson flipped the necessary switches to excite the wire strung between the top of Science Hall and the chimney of the old university heating plant behind it. He placed the phonograph needle on a record, and a receiver in Terry’s living room began to emit the faint sound of a piano playing “Narcissus,” a popular tune of the day.

The guests were underwhelmed. Years later, one of them said that she liked to think that all the guests “were as dumb about the whole thing as I was.” Not a single guest realized that one hundred years of broadcasting from the University of Wisconsin had just begun. The lack of enthusiasm in the Terry living room that night matched the lack of enthusiasm in the professor’s academic home, the physics department. Pioneer broadcaster Edgar “Pop” Gordon dubbed the department’s attitude “scornful.” The physics faculty prided themselves on the theoretical nature of their work and looked down on the “engineers,” who sought practical applications for their theories. Using radio gear to reach a broad audience had little to do with the physics of radio waves, and Terry’s colleagues punished his devotion to this peripheral activity.

The only other professor who shared Terry’s interest in radio and with whom he collaborated was, in fact, an engineer. In 1914, engineering professor Edward Bennett received a license from the federal government for experimental station 9XM, but he soon turned the project over to Terry, whose passion for the enterprise exceeded his own. The Wisconsin Idea, extending the boundaries of the university to the boundaries of the state, drove Terry to push beyond Morse code and make broadcasts accessible to anyone with a receiver. Transmission of voice and music required glass vacuum tubes, which were not yet manufactured commercially. The only way to get them was to blow molten glass into the shape needed, install the required electronics, and then remove the air from the tube to create a vacuum. The process presented many opportunities for failure, but Terry mastered the techniques and taught them to his students.

Partisans of the University of Wisconsin’s pioneering efforts in radio have proclaimed 9XM (later WHA) “the oldest station in the nation.” This boast headlines the historical marker affixed to Vilas Hall, which now houses public broadcasting on campus. In reality, no broadcast pioneer can identify precisely when a station began. Each station developed incrementally, starting with point-to-point messages in Morse code, eventually adding voice and music, inviting people to listen to these “broadcasts,” and, ultimately, producing a full schedule of broadcasts aimed at a broad audience. Wisconsin followed that progression. It was not until four years after 1917’s “first broadcast” that 9XM announced a limited broadcast schedule. It took ten more years to produce a full and reliable schedule.

Relicensed as WHA in 1922, 9XM’s significance in broadcast history has less to do with being first to broadcast than with being first to implement a public service philosophy of broadcasting. The two great progressive leaders, Professor Charles McCarthy and President Charles Van Hise, died before WHA replaced 9XM, but their Wisconsin Idea dominated the campus when Professor Terry started his work in 1910. [He] embraced the ideal of the university as an empowering force for all state residents. Unlike the engineers, physicists, and tinkerers who developed radio technology at other universities early in the twentieth century, Terry cared about the content his transmitter would broadcast. Terry understood that the real potential for radio was less about point-to-point communication (such as ship to shore) and more about reaching many people simultaneously, in “broadcasting.” He conceived of radio as a mass medium with receivers “more common than bathtubs in Wisconsin homes.”

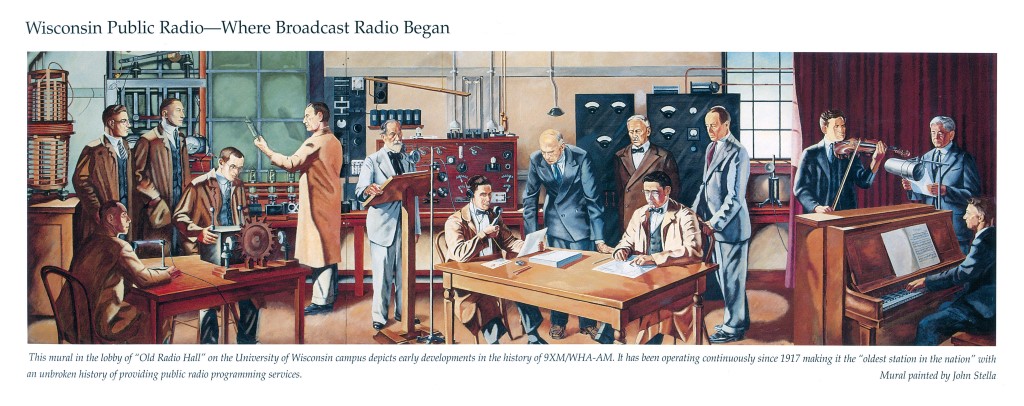

A mural by John Stella, still in UW-Madison’s Radio Hall today, celebrates the early days of radio. On the left are students and technicians. In the center are program director William Lighty (at podium) and chief operator Malcolm Hanson and station manager Earle Terry (seated at table). Standing behind them, left to right, are Radio Committee members Andy Hopkins, Edward Bennett and Henry Ewbank. On the right are early broadcasters, left to right, Waldemar Geltch, Pop Gordon and Paul Sanders. (Photo courtesy James Gill, Wisconsin Public Radio)

Terry accepted the appointment as the first manager of 9XM, a parttime assignment, in addition to his other professorial duties. With no budgeted staff, he needed to enlist the services of other faculty and graduate students to operate and program the station. He found coconspirators in Andrew “Andy” Hopkins of the Agriculture College and William Lighty, head of correspondence study for General Extension. Before radio broadcasting emerged as a useful technology, he “broadcast” useful information via available print media. When the Agriculture College created a Department of Agricultural Journalism to take over this function and to train students for media careers serving rural audiences, Hopkins became its chair and visionary leader. Like his peers in some other Midwestern universities, Hopkins saw radio as a better way to do what he was already doing in print. It was a perfect means of reaching the 190,000 small (seventy-acre or less) farms scattered throughout the state, particularly when the literacy rate among state farmers was only 60 percent. Even those who could not read English could understand it when they heard it on the radio. The station’s earliest transmissions in Morse code, and then voice, consisted of weather reports around the noon hour so that farmers could listen during their midday dinners. Market reports from the state department of agriculture followed the weather. Adding news from Hopkins’s agricultural journalism department created something like a noontime “farm” program.

Filling enough broadcast hours became an increasingly important challenge for Lighty. His concern was justified. In its first decade of operation, WHA’s programming consisted of the weather forecast, current prices for livestock and other agricultural products, and farm and home economics information for one hour at midday. The station returned to the air some evenings for an hour or two of educational talks, music appreciation, and live broadcasts of concerts and athletic events. The station needed to do much more to sustain its spot on the radio dial in the face of a frenzied gold rush for frequencies in the 1920s, when broadcasters realized they could get rich selling advertising around popular entertainment programs. A license to broadcast was virtually a license to print money and few not-for-profit broadcasters withstood the onslaught. In the view of the president of the University of Wisconsin [Glenn Frank] in 1935, the weak signal that failed to impress those gathered in Professor Terry’s living room in 1917 had acquired the power to become central to the future of democracy, to a more educated nation, and to a better understanding among diverse people. For the Wisconsin Idea to have any meaning at all, it had to use radio.

Read the 100-year anniversary story of how the “Wisconsin Idea,” and the public broadcasting system that began around it, grew into the future Frank foresaw in Jack Mitchell’s book “Wisconsin on the Air.”

This is an interesting story but a tough sell. There was a broadcast of opera from the Met, and a discussion of public radio at the time, in 1910.

Another relevant source:

9XM talking : WHA Radio and the Wisconsin idea / Davidson, Randall, 1959- / Madison: U of Wisconsin Press, 2006