Nonprofit Helps Homes Get Air Conditioned

36,500 Milwaukee homes lacked AC in 2019, mostly in low-income neighborhoods.

Freda Wright, a program manager for the Eras Senior Network, canvases Milwaukee’s Harambee neighborhood on July 20, 2022, connecting low-income elderly residents with free air conditioners and utility assistance. (Samantha McCabe / Wisconsin Watch)

It was only 10 a.m. and already above 80 degrees as Freda Wright slowly walked down a residential block of Milwaukee’s Harambee neighborhood, clutching a clipboard under one arm. Sweat beaded on her forehead as she navigated creaky front gates and porch steps during a scorching mid-July week when temperatures eclipsed 90 degrees.

Wright was canvassing the neighborhood on behalf of the Eras Senior Network, serving older adults of Milwaukee and Waukesha counties. The nonprofit received a $25,000 grant from Bader Philanthropies to purchase and install 100 air conditioning units over this year and next for qualifying seniors living in Harambee — free of charge.

The program addresses a long-unfulfilled need in Milwaukee, home to some of the state’s most vulnerable neighborhoods to extreme heat — where residents live in urban heat islands and struggle to afford air conditioning and their utility bills. About 36,500 homes in the Milwaukee metro area lacked any air conditioning as of 2019, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The homes are located disproportionately in neighborhoods where people of color live in deeply-segregated Milwaukee.

A banner hangs in the Harambee neighborhood on Milwaukee’s North Side. Neighborhood residents are among those in the city facing a “double whammy” of heat risks due to demographics and urban planning, says Steve Vavrus, a senior scientist with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Climatic Research. (Adam Carr / Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service)

As Wisconsin warms due to climate change, county and state officials have mapped the communities most prone to heat-related illnesses, educated residents about staying safe from the heat and directed the public to cooling sites during hot days. But cooling centers, while effective for some, don’t necessarily help those who lack transportation access or who are immobile. And Milwaukee County has just three public pools open this summer, with many others closed due to a lack of funding and lifeguards.

Meanwhile, Wisconsin’s main program for utility assistance focuses largely on heating aid during cold weather. During this year’s heat waves, the Biden administration suggested that states offer utility aid for cooling, but Wisconsin’s program is not set up to do so, typically running out of crisis utility aid before the end of each summer.

Air conditioning: an unmet need

Nearly one-third of Milwaukee households felt the negative effects of extreme heat last summer, according to a Wisconsin Department of Health Services assessment in collaboration with local organizations in Milwaukee. More than half at least sometimes felt too hot in their homes, and nearly one in 10 reported no forms of air conditioning.

A lack of affordable cooling is “a perennial problem” for lower-income Milwaukee residents, said Bob Waite, a senior account manager with IMPACT 211, a 24-hour phone and online helpline that connects local residents with information and resources.

“That’s going back more than 20 years,” Waite said. “It’s not a new thing that we don’t have a resource for somebody that’s in need of a free or low-cost air conditioner.”

Milwaukee residents have also texted News414, Wisconsin Watch’s engagement collaboration with Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service, to inquire about affordable air conditioning options.

‘The climate crisis is a health emergency’

Such needs will only grow in the coming Wisconsin summers. Temperatures across the Great Lakes region are rising faster than elsewhere in the United States as greenhouse gas emissions speed Earth’s warming. Extreme heat days in Wisconsin — hitting temperatures of 90-plus degrees — are projected to triple by the middle of the century, with 70-plus degree nights expected to quadruple, according to a sweeping Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts (WICCI) report released this year. For swaths of western and southern Wisconsin, that means temperatures hitting 90 degrees on 25 to 35 days each year by 2050.

Research shows that health impacts from extreme heat can be worse at night than during the day, leaving overheated bodies no chance to recover, said Steve Vavrus, a senior scientist with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Climatic Research and co-director of WICCI.

The elderly are particularly at risk. People older than 65 account for more than one-third of heat-related deaths nationwide, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

A man receives a box fan in Milwaukee during a July 1995 heat wave that saw temperatures reach as high as 103 degrees. The county medical examiner would attribute 91 deaths to the heat wave. That same heat wave killed hundreds more in Chicago, and it led communities across the country to adopt heat wave action plans. (Screenshot from 1995 TMJ4 News report)

Dr. Caitlin Rublee, a Milwaukee-based emergency medicine physician, said extreme heat is taking a toll on her patients, particularly those without air conditioning.

“They might not have air conditioning in their apartment complex, or they are trying to conserve costs and minimize their use of air conditioning just to make ends meet when it comes to their pocketbook,” she said.

Rublee added: “The climate crisis is a health emergency. I’m seeing adverse impacts, poor health, sick patients, every shift in the emergency department.”

The Milwaukee County Medical Examiner’s Office has attributed one death to heat this year: a 75-year-old woman who died in Wauwatosa in late June. Since 2008, the county has recorded 18 deaths related to overheating — 10 of those residents were older than 50.

A 2021 federal Environmental Protection Agency report notes that more than 11,000 Americans died from heat-related causes between 1979 and 2018, according to death certificates, but studies of extreme weather events suggest that related deaths may be undercounted.

“While dramatic increases in heat-related deaths are closely associated with the occurrence of hot temperatures and heat waves, these deaths may not be reported as ‘heat-related’ on death certificates,” the report reads.

Some still remember Milwaukee’s heat wave of 1995, when temperatures reached as high as 103 degrees during a stretch of mid-July. The medical examiner attributed 91 deaths to the heat wave, including that of an 82-year-old woman whose thermostat reached 90 degrees before she was found dead in her home.

That same heat wave killed hundreds more in Chicago, and it led communities across the country to adopt heat wave action plans. Milwaukee formalized its Extreme Heat Task Force in 2014 and revamped it as the Extreme Weather Task Force this year. It brings together local public health departments, housing authorities, nonprofits including the Red Cross and other groups to provide a localized, coordinated response to extreme heat.

Chicago offers dozens of cooling buses for immobile residents who need relief. Milwaukee County has not explored roving cooling buses, Paul Riegel, the director of the Office of Emergency Management’s Emergency Management Division told Wisconsin Watch, but added: “We will definitely look into it.”

‘Double-whammy’ of heat risk

The residents of Harambee, a majority Black neighborhood on Milwaukee’s North Side, are among those who face what Vavrus calls a “double-whammy” of heat risk due to demographics and urban planning.

Harambee is an urban heat island, where a concentration of pavement and buildings retains heat with little greenery to deflect the sun’s radiation or release moisture into the atmosphere. The population skews older than the rest of the city, and nearly half of residents have incomes below the federal poverty level. In other words, residents who are most vulnerable to heat tend to live in the hottest neighborhoods.

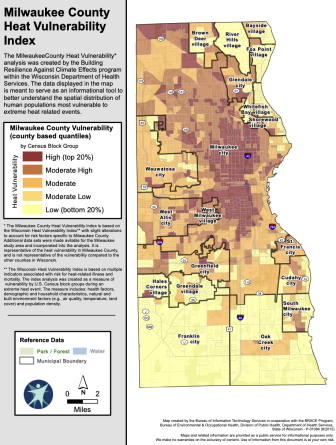

The Milwaukee County Heat Vulnerability Index, a color-coded map created by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services considers a range of demographic, health, household and environmental factors to assess residents’ vulnerability to extreme heat. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Department of Health Services)

Harambee sits in the top one-fifth of the most heat-vulnerable communities in Milwaukee County, as do a host of Black- and Latino-majority neighborhoods, according to the Milwaukee County Heat Vulnerability Index. The color-coded map created by the state health department considers a range of demographic, health, household and environmental factors.

Milwaukee’s Black and Hispanic/Latino households also tend to face higher energy burdens, meaning that a higher portion of their income pays off energy bills compared to white households.

Eras’ new program aims to combat energy burdens in Harambee, named in the 1970s for the Swahili word meaning “pulling together.” Wright had 15 air conditioners remaining as of mid-August, and Bader has committed to funding another 50 next summer. Eligible seniors can simply add their name and income to a brief application form.

For Wright, Harambee is her past and future. She still lives in her childhood house, just a few blocks away from King Solomon Missionary Baptist Church, where her father once pastored. So when the opportunity arose to become program manager for the Harambee neighborhood a few years into her tenure at Eras, she jumped at the chance.

“When this position came, it was perfect,” Wright said. “I get paid to find out where my people are at and how I can help. And that’s exactly what I did.”

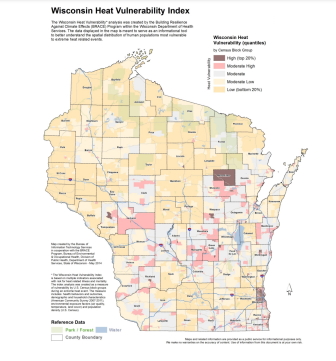

The Wisconsin Vulnerability Index shows that much of Milwaukee and Menominee Counties are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat due to a mix of demographic, health, household and environmental factors. (Wisconsin Department of Health Services) (Courtesy of Wisconsin Department of Health Services)

She knows that neighborhood seniors eligible for an air conditioner also need help affording extra energy costs. Recipients of air conditioners through the Eras program also receive $100 in utility bill assistance.

During this summer’s heat waves, the Biden administration has pointed to a federally funded, state-run program that could help ease energy burdens nationwide: the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), which has provided Americans nearly $9 billion in assistance during the 2021-22 fiscal year. That includes $96 million to Wisconsinites.

On July 19, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services sent a memo suggesting that states use LIHEAP to respond to heat, such as by adding or expanding cooling assistance, including by financing air conditioner purchases or repairs.

Funding for cooling sparse

But since Wisconsin’s program focuses on keeping families warm during cold winters, it has used up all available funding before it could go towards summer cooling, even after a boost from federal COVID-19 relief funds, confirmed Tatyana Warrick, a Wisconsin Department of Administration spokesperson.

Additionally, the state bars utilities from disconnecting customers who are behind on their bills during the cold weather season between Nov. 1 and April 15. No such broad moratorium for hot weather exists, although utilities may not disconnect customers when the National Weather Service issues a heat advisory.

Through the state home energy assistance program, called WHEAP, eligible Wisconsinites can seek an energy assistance payment once a year, or crisis assistance, which is metered out on a first-come, first-served basis. Residents can apply for regular energy assistance only from Oct. 1 to May 15. And the state’s pool of crisis assistance funding ran out in early July after benefitting 14,100 Wisconsin households over the previous two months. The federal government will not replenish those funds until Oct. 1, the new fiscal year.

Even though many more families apply for utility assistance during the winter, this timing is not ideal, said Diane Zettelmeier, acting program coordinator of the Milwaukee County Energy Assistance Program, which helps distribute the federal funds locally.

“Right now is a crisis time. So if people are facing a disconnect, this would be the time that they would normally apply, and we could help them with emergency funds,” she said. “The problem right now is that the state is out of crisis funding. So if people are coming to us, we don’t have a benefit to give them to not be disconnected.”

If funds were available, WHEAP wouldn’t offer crisis assistance for cooling unless a state or local public health official declared a heat emergency and the state’s Division of Energy, Housing and Community Resources authorized it.

Warrick said WHEAP could purchase air conditioning units for households under those circumstances, but only if they have a statement of need from a medical practitioner. The agency also is exploring ways to offer air conditioning repairs and replacement through its program when funds are available, Warrick said.

Raising awareness, seeking solutions

Amid Wisconsin’s shortage of home cooling assistance, researchers across the state are raising awareness of the heat-related dangers among the public and policymakers. Wisconsin DHS’s decade-old Climate and Health Program recently received an additional $400,000 a year for the next five years from the CDC, said Maggie Thelen, the program’s manager.

The funds will support communication and data analysis, such as DHS’s Heat Vulnerability Index, and a still-in-development Environmental Equity Tool to inform future community planning.

“There’s so much happening around climate change — and extreme heat — that it’s hard to figure out what’s all being done and make those connections,” Thelen said.

Wisconsin’s local governments most directly coordinate emergency responses, planning and hazard mitigation, Thelen added. In Milwaukee County, the Extreme Weather Task Force provides critical information to residents during heat waves.

“Policies that reduce energy expenses and reduce exposure to dangerous heat are healthy solutions,” she said, adding: “I think about landlords, especially for low-income housing, public health professionals, businesses and utilities companies coming together, and listening to the residents of urban and rural areas — to come up with solutions that are cost-effective and healthy.”

Vavrus called for climate-focused urban planning, such as increasing heat-absorbing vegetation in concrete-heavy swaths of the city.

“It’s no surprise, no secret that areas that are more wooded, more forested, more vegetated in general, don’t get as hot and those tend to be wealthier,” he said. “So it’s partly a resource problem that a lot of the poorest members of our society are the ones who suffer the most in terms of heat waves. A lot of it is needless.”

Wright remains focused on helping her neighbors in Harambee. She helped Eras raise more than $6,000 this summer to make it eligible for the $100,000 “A Community Thrives” national grant competition. Eras’ proposal focuses on helping low-income seniors in Milwaukee and Waukesha counties navigate extreme heat and utility bills.

“That’s what I always tell everybody,” she said. “Even if I can’t help you, I might know somebody, or I’ll figure it out. I’m the queen of trying to figure it out.”

As Midwest summers get hotter, Milwaukee’s most at risk have an unmet need: air conditioning was originally published by Wisconsin Watch