GOP Bill Assigns Electoral Votes by Congressional District

State Rep. Gary Tauchen's bill would put partisanship, gerrymandering "on steroids."

If Wisconsin had picked its Electoral College delegates using a congressional district method, President Donald Trump would have received the majority of Wisconsin’s 10 votes in 2020. Six, to be precise.

And that is what a new bill authored by Rep. Gary Tauchen (R-Bonduel) would do. It would make Wisconsin a state where the winner of the popular vote does not get all — or even necessarily the most — Electoral College votes. Tauchen’s bill (LRB 0513/1) would distribute the presidential electors by assigning one vote for each of Wisconsin’s eight congressional districts, then giving the remaining two electors to the statewide winner of the popular vote.

That would exacerbate partisanship and give added incentive to gerrymander the map of Wisconsin’s congressional districts to favor one party over the other, says UW-Madison Prof. Barry Burden, founder and director of the Elections Research Center.

“Doing it by congressional district is actually a terrible idea, because what it will do is amp up the partisan efforts to draw those districts to favor one side or the other,” says Burden. “It’s already an ugly process, but it will be on steroids if those districts affect not only control of Congress but also control the presidency.”

That’s not how Tauchen sees it. He has not responded for comment, but in his memo seeking other representatives to cosponsor his bill, he claims it would be progressive.

“Given the numerous political views and progressive history, this alternative distribution system would better reflect Wisconsin’s diverse political landscape,” he writes. The winner of a congressional district would be “awarded that district’s sole elector.”

Burden says he sees the surface-level initial appeal at the idea of the parties sharing and each having some electors from the state. But that’s not how it would work, in reality, for Wisconsin. Because the congressional districts are gerrymandered by Republicans to favor Republicans, five of the eight districts are held by Republicans. Democratic U.S. Rep. Ron Kind’s district in western Wisconsin also went to Trump in both 2016 and 2020, although Kind has continued to be elected to Congress, however with shrinking margins as rural Wisconsin gets more Republican and suburbs lean increasingly toward Democrats.

“There would suddenly be interest in parties trying to control every little district that right now is of no consequence for controlling Congress, even,” adds Burden. “But in Wisconsin it would be both. And so I worried that it would actually exacerbate the partisan wrangling over election rules. And that’s one thing we don’t do more of at this point.”

Tauchen began circulating his bill on Jan. 5, one day before pro-Trump rioters broke into the U.S. Capitol, egged on by Republican lies and distortions about a stolen election.

The bill was introduced once before, in 2007, with Tauchen as the author and it died in committee. That same year, he also introduced a bill to eliminate voters’ ability to vote a straight-party ticket. The bill is an unusual fit for the 67-year-old dairy farmer, who graduated from the UW-River Falls with a degree in animal science in 1976 and chairs the Assembly Committee on Agriculture. His more recent portfolio of bills from last session includes measures concerning livestock facilities, bulk milk weighing, requiring retailers to accept cash and declaring a Howard Temin day.

But in the current session, changing election laws will be an Assembly Republican top priority, according to Speaker Robin Vos, who emphasized its importance in his inaugural address. “Wisconsin learned over the last year that we must restore confidence in the electoral process,” said Vos. “I invite every single legislator on both sides of the aisle to join our efforts. We want to put these important innovations into law and into practice.”

Interstate Popular Vote Compact

Another state that has seen a push for voting by congressional district, according to Burden, is California, where some Republicans expressed interest in the idea hoping that out of the state’s 55 votes, “they might at least get 15 or 20 of those, which would be a huge increase.” But it never progressed, he says.

An idea that has gotten more traction, notes Burden, is the Interstate Popular Vote Compact.

“That’s an agreement among the states that they would give all of their state’s electoral votes to whoever wins the national popular vote,” he explains. “So if you sign on to this agreement as a state, regardless of what happened with a vote in your state on Election Day, if the Republicans won the national popular vote, you would give your state’s electors to the Republicans. So, it would essentially turn the election into a popular vote election, because the Electoral College would always go with the winner of the popular vote.”

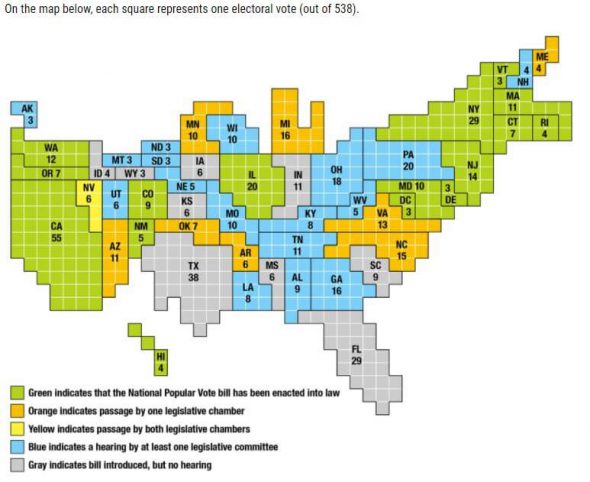

A map by Electoral College votes showing states that have enacted legislation advocated by NationalPopularVote.com

If enough states were to adopt this method to constitute a majority of Electoral College votes, it would make the winner of the popular vote the next president. The bill goes into effect if it is enacted into law by states possessing 270 electoral votes — a majority of the 538 total votes. It would then be in place for the next presidential election.

As of July 2020, 16 jurisdictions possessing 196 electoral votes had signed on by passing legislation, according to NationalPopularVote.com, which states on its website, “it has been enacted into law in 16 jurisdictions possessing 196 electoral votes, including 4 small states (DE, HI, RI, VT), 8 medium-sized states (CO, CT, MD, MA, NJ, NM, OR, WA), 3 big states (CA, IL, NY), and the District of Columbia. The bill will take effect when enacted by states possessing an additional 74 electoral votes.”

As Tauchen’s bill shows, states can choose how to allocate their votes.

A bill switching to the popular vote ratification method was most recently introduced in April 2019 in Wisconsin, sponsored by Rep. Gary Hebl (D-Sun Prairie) and former Sen. Dave Hansen. It died without a public hearing or being considered in the Republican-controlled Committee on Campaigns and Elections. At its first introduction in 2008, there was a hearing on a similar bill and a survey at the time showed 71% support in the state, including 63% of Republicans and 81% of Democrats.

It would be a hard sell among Wisconsin Republicans, however, because not only has the national popular vote favored Democrats in the recent past, but it would mean giving up all the attention Wisconsin enjoyed in the 2020 campaign.

“It tends to be blue states — it’s very hard for a swing state to give up its status,” says Burden. “But it would make all the worries about the Electoral College — the kind of lawsuits that have been focused on the swing states and all the controversy in places like Wisconsin and Georgia and Pennsylvania — would go away, because it would be the national popular vote that would determine who gets the majority of the electors.

“So that’s a reform I think that’s more promising.”

Reprinted with permission of Wisconsin Examiner.