Story of State’s First Coronavirus Case

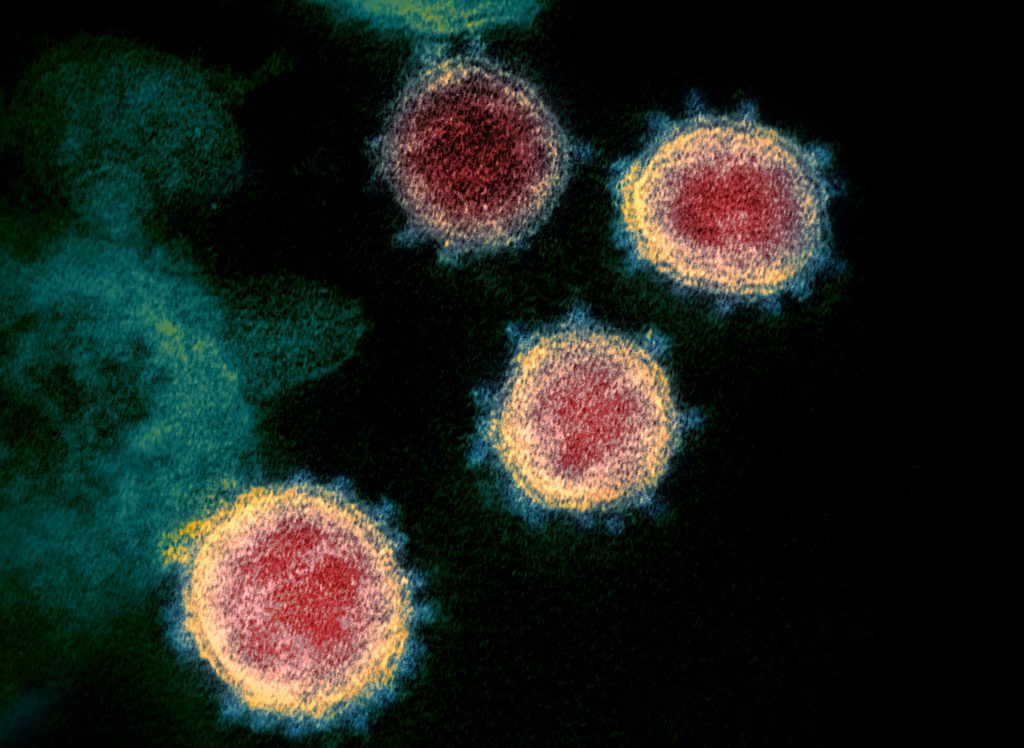

Nation’s 12th case; virus now being studied at UW-Madison research lab.

A scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 viruses (in gold) emerging from the surface of cells cultured in the lab. SARS-CoV-2, also known as 2019-nCoV, is the virus that causes COVID-19. The virus shown was isolated from a patient in the U.S. Image from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/Rocky Mountain Laboratories (CC BY 2.0).

A serious new respiratory illness is gaining steam around the world, and epidemiologists, virologists and many other scientists are sprinting to learn as much as they can about it as quickly as possible. Named COVID-19, the disease emerged in China, with cases spreading rapidly in Iran, Italy and South Korea, among other places. Its advance poses a “tremendous public health threat,” according to a United States health official leading the nation’s response to the outbreak.

But the novel coronavirus that causes the illness — the pathogen is officially called SARS-CoV-2 — also presents a unique and urgent research opportunity to scientists who study infectious diseases, at least when they’re able to get their hands on it.

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 on American soil was identified in Washington state on Jan. 21, 2020. Scientists working on behalf of the National Institutes of Health relied on the virus contracted by this patient to develop lab-grade specimens for distribution to researchers across the nation.

Given the urgency of uncovering as much as can be learned about the virus and the disease it causes, infectious disease researchers in Madison snapped into action immediately.

What is known publicly about the case in Wisconsin is that a traveler arrived on a flight at the Dane County Regional Airport in Madison in late January, experiencing symptoms that aligned with the new disease. Common symptoms of COVID-19 are fever, coughing and shortness of breath. Returning from a trip that included time in Beijing and contact with people known to have been diagnosed with the illness, the traveler proceeded directly to the emergency room at the University Hospital from the airport. While there, doctors isolated the patient and took specimens from their respiratory tract for testing at Centers for Disease Control and Prevention labs in Atlanta.

Meanwhile, the patient was sent home for isolation and their family was quarantined, and the CDC subsequently confirmed the infection.

Less than a week later, the University of Wisconsin-Madison announced SARS-CoV-2-related research was in the works on campus. These efforts would include research by professors Thomas Friedrich and Dave O’Connor, who hope to better understand how viruses like SARS-CoV-2 enter the human population, among other goals. The virus is believed to have originated in an animal species and made the jump to humans in the city of Wuhan in central China, at a market where wild animals were sold for consumption alongside produce and livestock.

“We’d like to know why these sort of events happen,” said Friedrich in a Feb. 13 interview on PBS Wisconsin’s Here & Now.

“About 75% of major human infectious diseases, according to one estimate, come originally from animals like this virus is thought to do,” he said. “But there are millions of viruses and parasites and bacteria infecting animals that never become major human diseases. So, we like to understand when we see a new example of this — how it came to be.”

Friedrich and O’Connor are coordinating their plans with researchers at other labs around the nation. Those plans will depend on one of those collaborators receiving a specimen of the virus, likely through the federal government, since Friedrich and O’Connor do not have facilities equipped to handle it. But another UW-Madison researcher who does operate such a lab was able to lock down a more local source of the virus.

Getting access to dangerous pathogens

Within days of Wisconsin’s first confirmed COVID-19 infection, a sample of the virus drawn from the Dane County patient that was not sent to CDC would be housed within the highly secure laboratory of Yoshihiro Kawaoka, a prominent UW-Madison researcher known for his sometimes controversial work on other deadly viruses including ebola and the H5N1 subtype of influenza A. Kawaoka hopes to identify an appropriate animal model for the virus, a key step in documenting its transmissibility and lethality, and for testing potential treatments and vaccines.

This swift access to a local specimen was a matter of scientific serendipity and stands in contrast to how most researchers in the U.S. are able to access SARS-CoV-2. It highlights how the race to understand the virus can be as much of a game of chance as the efforts to contain it.

There are many important questions surrounding SARS-CoV-2, from the way it attacks healthy cells to the range of symptoms it can cause and how long it can survive outside of its hosts. The ability to answer any of these questions with confidence depends on having viable samples of the virus for conducting laboratory experiments.

As the illness has emerged over the early weeks of 2020, most researchers in the U.S. have to wait for the Manassas, Virginia-based Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository to approve a request and send a specimen from its limited supply. The repository is operated by American Type Culture Collection, a life sciences non-profit that provides the specimens to researchers via a contract with the NIH. While specimens are free for approved labs, the repository is generally limiting shipments to one specimen per lab twice a year and is not guaranteeing a shipping timeframe.

Additionally, the repository is offering specimens only to labs with a biosafety level 3, or BSL-3, rating. Such labs are relatively uncommon, must be designed to be self-contained, and workers must adhere to extremely strict safety standards.

Kawaoka’s facility in Madison includes a laboratory suite rated as BSL-3Ag. This designation means the lab adheres to even higher engineering and biosafety standards than a BSL-3 facility and has the capabilities to house research on highly dangerous pathogens.

Having the proper facilities is only one requirement among many to which researchers must adhere in order to gain access to pathogens like SARS-CoV-2. In fact, Kawaoka’s request for a specimen from the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics involved at least as many permissions and logistical hurdles to clear as would be required to receive a specimen from the Biodefense and Emerging Infections Research Resources Repository.

Dressed in personal protective equipment with an integrated breathing system, a researcher demonstrates proper lab biosafety practices for a group of media representatives touring the Influenza Research Institute at the University of Wisconsin-Madison on Feb. 28, 2017. The high-security research facility operated by Yoshihiro Kawaoka was closed down for annual decontamination, cleaning and maintenance. Photo by Jeff Miller/UW-Madison.

For starters, Kawaoka had to gain permission to access the specimen through the UW’s Health Sciences Institutional Review Boards, called IRBs for short.

IRBs are commonplace at research institutions in the U.S. and help ensure that medical research involving human subjects is performed according to federal and state laws, university policies and professional ethical standards.

But IRB approval is only one aspect of a logistical landscape that governs how potentially dangerous specimens make their way from a hospital to a UW research lab.

Safdar said prospective researchers must submit a protocol describing how they intend to use a specimen, how they will protect the confidentiality and privacy of the individuals who produced the specimen, and how the specimen will be stored along with many other details.

Once the IRB has signed off on a protocol, qualified technicians at the hospital will prepare the specimen for shipment.

The logistics of a shipment depend on the type of pathogen being shipped. For instance, viruses that are considered most dangerous to the health of humans, animals or plants are classified as Federal Select Agents and are subject to particularly stringent regulations surrounding their handling and shipment.

“The transfer must happen within a specific time window with the required notifications,” wrote Rebecca Moritz in an email to WisContext. Moritz is UW-Madison’s responsible official for Federal Select Agents and helps ensure that biosafety and biosecurity practices are being adhered to at labs including Kawaoka’s.

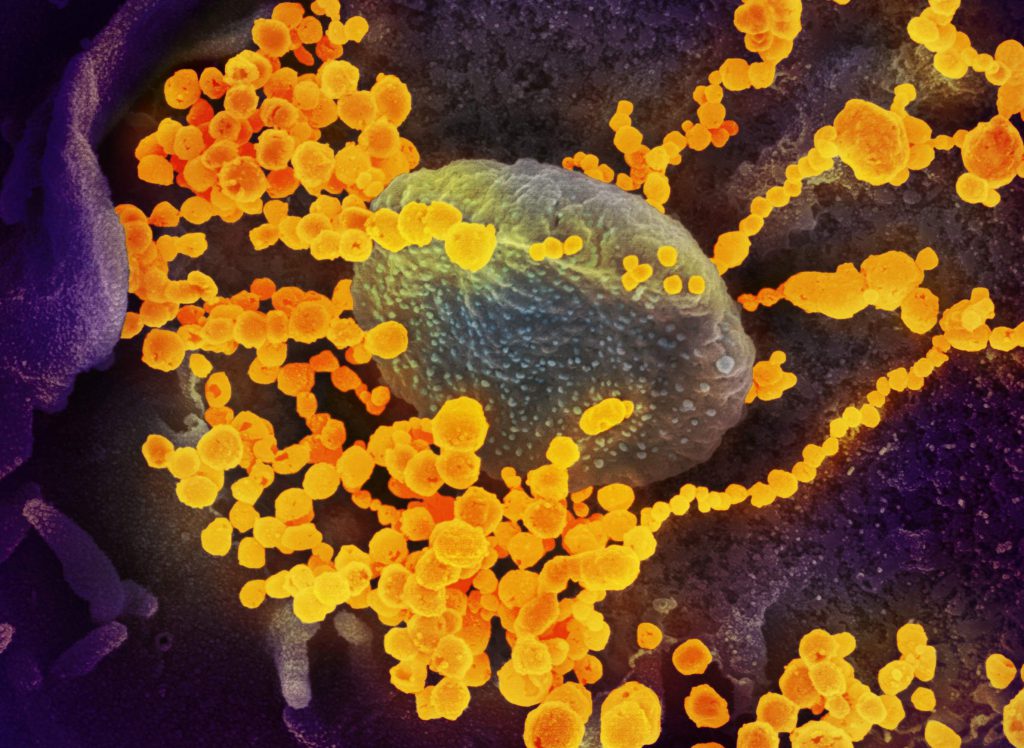

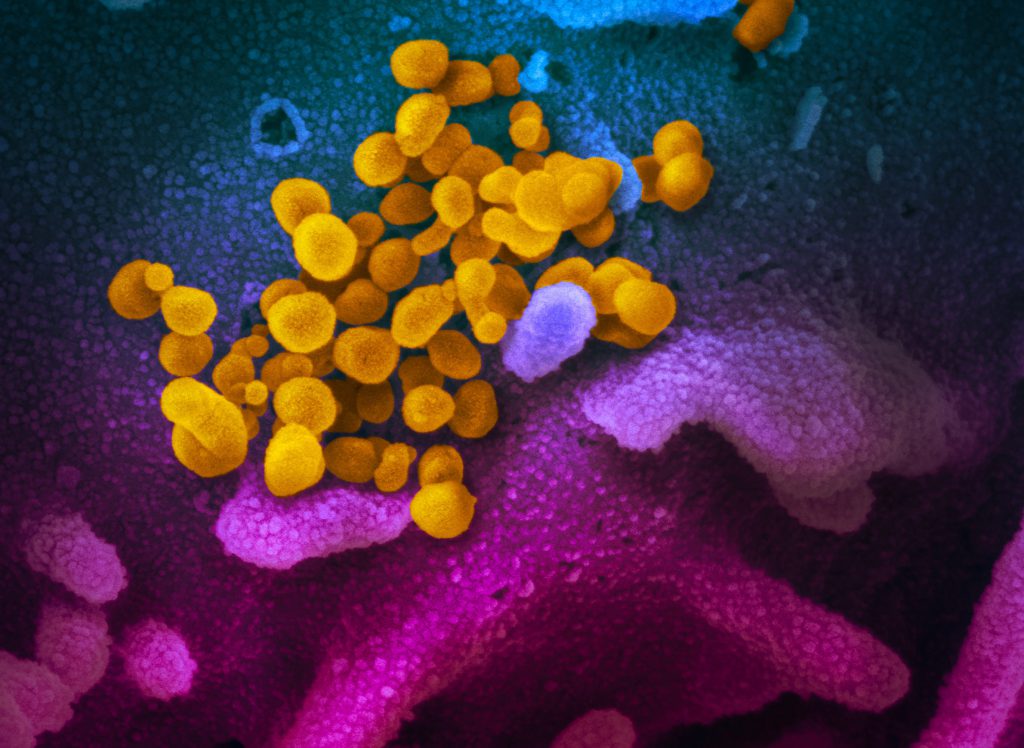

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 viruses (yellow) emerging from the surface of cells (blue and pink) cultured in the lab. The federal government has mandated significant biosafety precautions for researchers working with the virus. Image from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases/Rocky Mountain Laboratories (CC BY 2.0).

Moritz said that even pathogens not identified as select agents, which includes SARS-CoV-2, are subject to biohazard shipping regulations enforced by the U.S. Department of Transportation or the International Air Transport Association, depending on the mode of shipment. She said that shipping permits may also apply and that the DOT requires shippers to be trained to ship hazardous biological substances.

“For some materials, shipping permits are required even between researchers at the same institution,” she said.

In a reflection of the seriousness of the issue, DOT may impose penalties for improper shipping of hazardous materials that amount to nearly $80,000 per day, per violation.

These same regulations apply to potentially dangerous specimens no matter where they originate in the U.S., and additional state laws may impose further requirements. On top of that, the NIH and and CDC compile biosafety best practices and policies for labs working with specific pathogens. This includes the CDC’s Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories reference guide.

A statewide resource for pathogens

Another archive of disease-causing pathogens is the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, which is also located on the UW-Madison campus. The state hygiene lab plays a key role in monitoring disease outbreaks by testing specimens sent in from clinics and hospitals across Wisconsin. The lab is not testing for SARS-CoV-2 as of February 2020 — testing for the emerging disease has so far been a sole responsibility of the CDC — but it regularly performs diagnostic tests on patient specimens for all sorts of pathogens.

“We gather a lot of specimens from the various surveillance programs and various outbreaks we’ve worked on, and we always save our residual specimens,” said Peter Shult, who leads the lab’s communicable disease division.

Shult described a couple scenarios under which the state hygiene lab shares its specimens with outside labs.

The first is related to confirming the accuracy of new diagnostic techniques. Because the lab maintains a large repository of specimens that test positive or negative for various diseases, those with known results are useful for confirming the accuracy of new ways of diagnosing patients. Those specimens are often related to common infectious diseases.

But the state hygiene lab also houses specimens of rarer and more dangerous pathogens of high research value.

“Researchers we might find on the UW campus or others that we have association with around the state [are] also interested in getting some of our positive specimens, but ones that are a little more unique,” Shult said.

A “freezer farm” in the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene — located in a locked room and accessible only to certain staff — serves as a repository for pathogens researchers might want to study. Each freezer contains thousands of specimens. Photo by Jan Klawitter/Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene.

One past example involves the pandemic-causing 2009 swine flu and a familiar researcher.

“Very early on [in the pandemic] we identified positive specimens using the tests that CDC had put together for us, and we were almost immediately contacted by Yoshi [Kawaoka] on campus,” Shult said.

In that instance, Kawaoka, who declined an interview for this story citing a lack of time, had requested a specimen to begin some basic research characterizing the virus and how it is related to other influenza subtypes.

For researchers hoping to secure one of the state hygiene lab’s more dangerous specimens, Shult detailed a process similar to that at UW Hospitals and Clinics. Researchers must provide detailed information in writing that describes the research they plan to perform with a specimen, the biosafety practices within the lab where the research will take place, and other information required by law. These requests are also subject to the lab’s own IRB approval process.

Shult noted select researchers around Wisconsin have developed high levels of trust with the state hygiene lab over the years, a key element in any successful relationship — particularly one with such high public health consequences.

“It’s a great relationship to have with researchers,” he said. “Because we do have unique access to these specimens and these microorganisms that they might not otherwise get access to themselves.”

Building trust in these relationships can go beyond adhering to laws and ethical standards. It also helps to develop a lab culture that mandates doing everything reasonable to reduce risk, even as COVID-19 infections and related deaths increase around the world and the CDC warns that the disease’s spread in the U.S. appears inevitable.

Even as the disease continues to spread, the Kawaoka lab is taking special precautions with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Rebecca Moritz, the UW-Madison biosafety official, said risk reduction efforts include requiring technicians who work with the virus to be screened often and regularly for symptoms of COVID-19. The technicians have also agreed to remain within Wisconsin’s borders following any work with the virus for at least 14 days — the upper limit of what is believed to be the disease’s incubation period.

The Scientific Serendipity Of Wisconsin’s First Novel Coronavirus Case was originally published on WisContext which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio and PBS Wisconsin.