How Non-Partisan Are Supreme Court Races?

Not very, the data suggests. Is there any way to change this?

Wisconsinites have two separate election cycles. One is for elected positions designated as partisan, with the general election occurring in November of even-numbered years. It combines state elections for governor and legislators with elections for federal offices.

The second election cycle is for positions designated as nonpartisan. These general elections occur in April of most years and cover a broad array of offices, including judges, the state superintendent of schools, and most local offices: mayor, school boards, etc. The architects of Wisconsin’s election system hoped to remove certain elected officials from partisan politics.

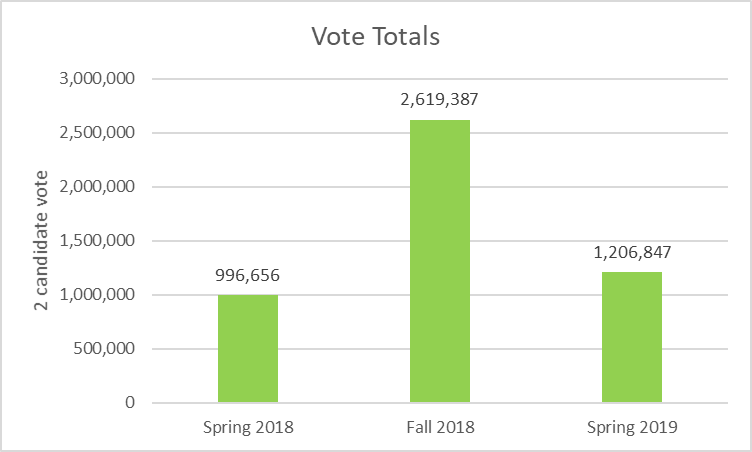

One result of this split is that candidates for nonpartisan offices are elected in low-turnout elections. Here are the vote totals for the most recent Wisconsin elections — the nonpartisan election in spring 2018, the partisan election in November 2018, and the nonpartisan election last April. These totals are for the two leading candidates for the state supreme court in the nonpartisan elections and for governor in the partisan election.

As you can see, the turnout for the partisan election, in the middle of the graph, is double that for the non-partisan elections. That’s the prevailing pattern, except when the spring election includes the Wisconsin presidential primary. Particularly as American politics has become more tribal, these elections may be won or lost by which tribe can turn out more of its members, rather than who would make for the fairer judge or effective school board member. The winner may depend on who is most effective at turning out its base.

The recent Supreme Court race in which Brian Hagedorn pulled out an unexpected victory against Lisa Neubauer reflects the increasing polarization of Wisconsin’s highest court. Early on, Neubauer seemed to have a clear path to election. She was clearly respected by her colleagues on the courts and regarded as nonpartisan, as reflected both in the endorsements from fellow judges and her election as chief judge of the Court of Appeals and a member of its Waukesha-based District II.

Hagedorn had a record of anti-gay blog posts and his association with a school that banned gay faculty and students. As recounted by Bill Kaplan in Urban Milwaukee and the Journal Sentinel’s Dan Bice, this record caused several organizations whose support Hagedorn might have expected to count on—such as the Wisconsin realtors’ association, Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce, and the US Chambers of Commerce–to sit out the election.

Liberal groups jumped on Hagedorn’s apparent intolerance. For example, here is how the Wisconsin Democracy Campaign described ads from the Greater Wisconsin Committee:

In early March, the committee sponsored a 30-second television ad that questioned the fairness of conservative Appeals Judge Brian Hagedorn following media reports about Hagedorn’s past blog posts, speeches, and his connection to a school that where employees and students can be fired or expelled for being gay.

Meanwhile, several conservative groups jumped in the race to support Hagedorn. Wisconsin Family Action attacked Neubauer for her endorsement by Planned Parenthood and the Human Rights Campaign. Likewise, the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity, while arguing that “WISCONSIN DESERVES A NONPARTISAN SUPREME COURT” and describing Hagedorn as “NONPARTISAN. IMPARTIAL. FAIR,” also pointed out that he was appointed by Scott Walker.

As a result, the race evolved from who would make the most thoughtful justice, to which groups could most effectively turn out their base. The Supreme Court election became a partisan election in every way except for its label.

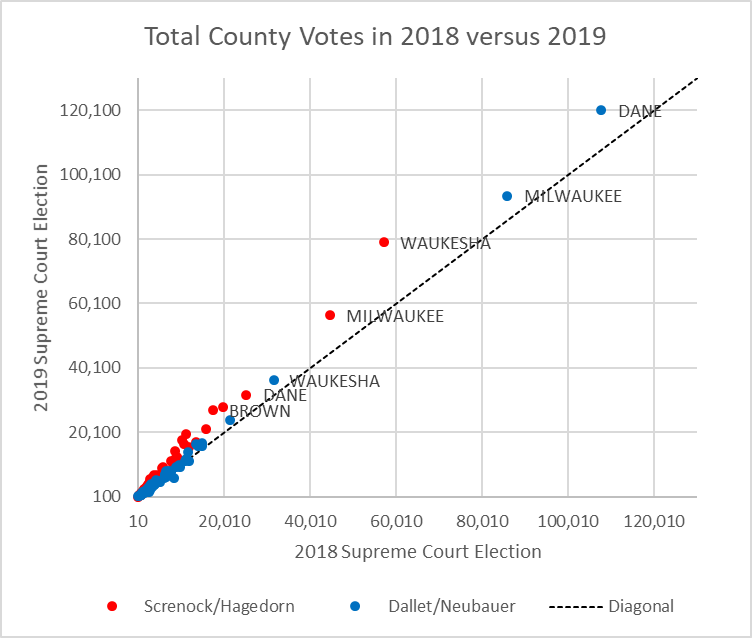

The plot below compares the county vote in 2018–on the horizontal axis–with the 2019 vote—on the vertical axis. Votes for Michael Screnock and Hagedorn are shown in red; those for Rebecca Dallet and Neubauer in blue. Both the blue and the red party increased its turnout in the 2019 election won by Hagedorn, as shown by points above the dotted line, the diagonal.

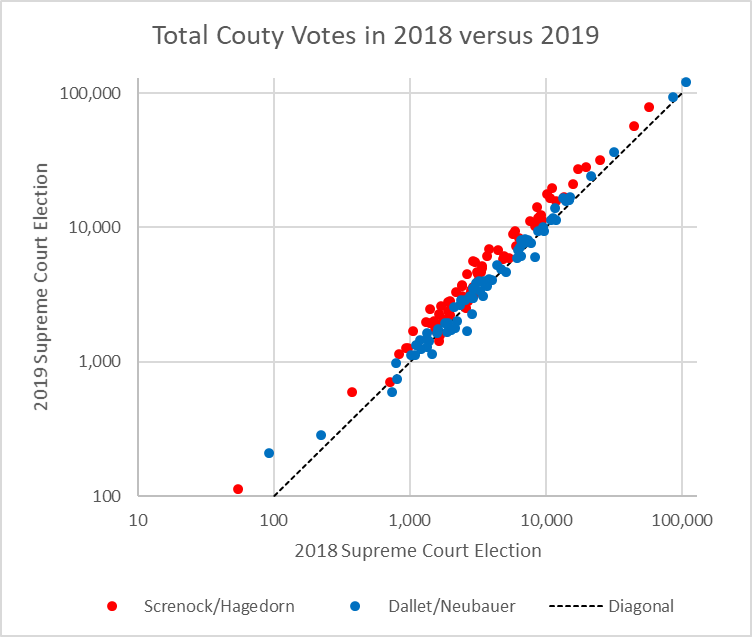

The next chart shows the same data as above but uses logarithmic scales. This has the effect of shrinking the votes of large counties and expanding those of small counties. Note that for almost every county the red party had a greater increase than the blue party, reflecting the red party’s greater success in turning out its base.

Contrary to the hopes of those separating nonpartisan and partisan elections, this separation does not eliminate partisan voting. Instead it hold downs the turnout. As the next chart shows, in Milwaukee only 22 percent of registered voters bothered to vote for either Supreme Court candidate. Thus, success comes not to the candidate who is least partisan but to the one whose supporters are most skilled at turning out the partisan base.

Separating elections for nonpartisan offices from those for partisan offices, has not kept partisanship out of Wisconsin’s Supreme Court. It has, however, held down voter participation. Perhaps it is time to move all Wisconsin’s elections to a time when most registered voters are likely to show up. While moving the elections for nonpartisan offices to the same date in November as partisan elections would not eliminate partisanship, it would at least help assure that the result comes closer to the consensus of all voters.

Can Wisconsin regain its nonpartisan Supreme Court? I would say the prognosis is discouraging. So long as powerful groups want to use the court to advance their agendas, it is likely we will continue to elect partisan hacks with extreme positions—as Hagedorn shows every sign of being. Restrictions on spending—or public spending—would help, combined with a strong ethics code that requires justices to recuse themselves when a party before them is also a significant political contributor. But the current Legislature —and Supreme Court majority — would not support this. At best it’s a hope for the future, that Wisconsin could some day regain a nonpartisan court that is not beholden to special interests.

Data Wonk

-

Scott Walker’s Misleading Use of Job Data

Apr 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Apr 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Partisan Divide on Education Hurts State

Mar 27th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Mar 27th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Will Wisconsin Supreme Court Legalize Absentee Ballot Boxes?

Mar 20th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Mar 20th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Ban all radio and television advertising for 60 days prior to the election.