New State Law Conceals Nursing Home Violations

Tort reform puts residents at risk, and makes criminal prosecutions of abuse and neglect more difficult, critics say.

A Wisconsin tort reform law passed two years ago made state inspection reports of nursing homes and other health care facilities inadmissible as evidence in civil and criminal cases. Proponents of the law say it lets providers discuss problems more openly, but critics argue it puts the elderly and vulnerable at risk. This woman, whose family asked that she not be identified, was a resident at a Sauk City nursing home. Lukas Keapproth/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

A FRAIL SYSTEM

About this series:

Families’ abilities to hold potentially negligent nursing facilities accountable have been diminished by a recent change in state law that bars records of abuse and neglect from use in the courts, the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism has found. The Center’s investigation also shows that some long-term care facilities are failing to report deaths and injuries, as required by law.

This project, A Frail System, explores those issues and offers families help in identifying which of the state’s nursing homes have been sued or cited for major problems.

DAY 1: New State Law Conceals Nursing Home Violations

Day 2: Nursing homes fail to report deaths, injuries

Sidebars:

- What to do if you suspect neglect or abuse

- How tort reform bill changed state law

- How to find nursing home inspection reports

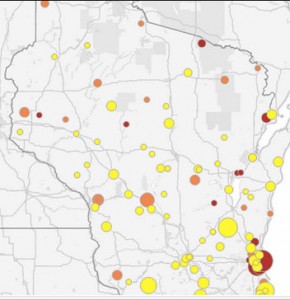

Interactive map: Nursing home violations in Wisconsin

Click to explore our interactive map.

Watch: Gov. Scott Walker talks about the tort reform bill

Joshua Wahl’s life had never been easy. But he was happy, his mother said.

Wahl has spina bifida, is brain damaged and paralyzed from the chest down. At age 32, he lived at a group home in Menomonie, where he loved coloring and going on picnics, said his mother, Karen Nichols-Palmerton.

One evening in October 2011, she visited the home and found her son’s room empty.

Wahl had been rushed to the hospital for treatment of a bedsore so severe that doctors feared he would be permanently bedridden.

A state health department investigation report later found he had the bedsore for four months before being hospitalized.

But the staff who cared for Wahl never sought medical attention for his wound, state investigation records show. And the facility never told the state or Nichols-Palmerton about it, as required by state law, according to state officials.

Instead, caregivers at Aurora Residential Alternatives sprinkled the bedsore with baby powder and applied antibiotic cream, watching it grow larger and more serious until it was bone-deep, records show. Nichols-Palmerton is suing Aurora for alleged negligence, seeking punitive and compensatory damages.

Changes to Wisconsin law passed two years ago, however, mean her attorney can’t use those state investigation records as evidence in the lawsuit, which alleges a four-month pattern of neglect.

“It scares me for those who put their trust in a facility,” said Nichols-Palmerton, who lives in Menomonie, a small city in western Wisconsin. “It scares me to think of things that could be brushed aside. I don’t rest so easy anymore.”

Holly Hakes, Aurora’s executive director, declined to comment, citing the pending litigation.

The law, which went into effect in February 2011, bars families from using state health investigation records in state civil suits filed against long-term providers, including nursing homes and hospices. It also makes such records inadmissible in criminal cases against health care providers accused of neglecting or abusing patients.

The changes were included in a tort reform measure, the first bill Gov. Scott Walker proposed after Republicans swept both houses and the governor’s office in the 2010 elections.

Proponents of the law argue that its impact on the use of investigation records is minimal. They point out that attorneys can still view state inspection reports and produce other evidence and testimony to document alleged abuse and neglect. In January, the Department of Health Services began publishing these reports online; records are available from July 2012 onward.

Some Democratic lawmakers, trial lawyers and advocates for the elderly questioned the push to pass Wisconsin Act 2, which they argued was harmful and unnecessary.

Critics say the law removes a useful tool for ferreting out abuse and neglect, noting that attorneys cannot use state inspection reports to affirm allegations or impeach witnesses.

“When you’ve got these records that are part of the regulatory process, the idea that you wouldn’t be able to introduce them to the jury is just insane,” said Milwaukee personal injury attorney Ann Jacobs. “Why would we hold that information back?”

That’s a major obstacle to protecting the elderly and other vulnerable people from harm, said Monica Murphy, an attorney with Disability Rights Wisconsin, a nonprofit advocacy group that opposed the bill.

“There are witness statements in state inspection reports. You can’t replace those,” said Dane County Circuit Judge William Hanrahan, who prosecuted crimes against the elderly for 19 years as a district attorney and an assistant attorney general. Photo courtesy of countyofdane.com.

“These people often don’t have the capacity to testify about what happened to them,” Murphy said of the nursing home residents affected by the change. “Having access to state reports is key to correcting negligence and prosecuting criminals.”

At least 270 tort reform laws have sprung up in 49 states since 1990, a Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism analysis found. Some, including the one in Wisconsin, can be traced to the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, a group funded by private industry that develops pro-business model legislation used primarily by Republican lawmakers.

‘I was shocked’

Nichols-Palmerton thought she knew what was going on at Aurora. She chose the group home for her son after consulting with social workers and special education teachers. For five years, Wahl did well there. During twice-weekly visits, she talked with caretakers about his treatment.

“I thought I was very involved,” she said. “The staff told me he looked great, he was doing great.”

When she visited Aurora the evening of Oct. 28, 2011 and found Wahl’s room empty, she was told he had been taken to the emergency room at Red Cedar Medical Center in Menomonie for treatment of a bedsore.

Also known as pressure ulcers, bedsores are a dangerous problem in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, where some residents are confined to beds or wheelchairs or can’t easily reposition themselves on their own. Such wounds are caused by sustained pressure and friction that cuts off blood supply, killing underlying tissue and muscle.

If caught and treated early, bedsores are not life-threatening. But without treatment they can lead to fatal complications, including cancer, sepsis, meningitis and other bacterial infections.

When Nichols-Palmerton arrived at the hospital, she found a crater the size of a half-dollar on her son’s buttocks. Skin, fat and muscle had rotted away. The wound was a quarter-inch deep and contaminated with feces.

“I can’t believe it went so long without someone paying attention to it,” said Nichols-Palmerton, who herself works part-time as a caregiver at another Aurora facility in Menomonie. “I was shocked.”

Doctors told her the bedsore was Stage IV, the most serious, and that her son had E. coli, bone and staph infections. He needed surgery, and his recovery would be slow and painful. They worried he might never be able to sit in his wheelchair again.

Bill’s goal was jobs

Opponents of the tort reform bill testifying at a public hearing in January 2011 said the new law would shield health care providers that allegedly neglect or abuse patients.

But supporters said the bill would help fuel the economy by reducing corporate litigation costs.

In a Dec. 19 interview with the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism, Gov. Scott Walker defended the tort reform law he proposed and lawmakers passed in January 2011, saying it was needed to forestall “this constant pattern of litigation” that could be seen as a negative by employers. Here Walker is pictured in December 2011. Lukas Keapproth/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

“Each of these (proposals) is aimed at one thing — jobs,” Brian Hagedorn, Walker’s chief legal counsel, said at the hearing. “These changes send a symbolic and substantive message that Wisconsin is open for business.”

None of the bill’s 30 Republican coauthors and cosponsors testified at the hearing, which stretched 10 hours.

One of the bill’s top legislative sponsors, then-Sen. Rich Zipperer, R-Pewaukee, declined to be interviewed for this report. Rep. Jim Ott, R-Mequon, who introduced the bill with Zipperer, did not respond to repeated interview requests.

Proponents of the change, including the Wisconsin Hospital Association and Wisconsin Medical Society, argue that barring use of state investigation records in lawsuits and prosecutions lets providers discuss problems more openly, thereby improving patient care.

“Now they can have that conversation without fearing (a personal injury attorney) is going to come read it” and use the statement in a lawsuit, said Brian Purtell, an attorney with the Wisconsin Health Care Association, a nonprofit group that represents long-term care providers.

In a Dec. 19 interview with the Center, Walker defended the new law, saying it was needed to forestall “this constant pattern of litigation” that could be seen as a negative by employers. He added that “frivolous lawsuits (are) a huge barrier to economic growth and development.”

Darren McKinney, a spokesman for the American Tort Reform Association, a Washington, D.C. advocacy group, agreed, calling the law an important step in preventing meritless lawsuits.

“No one in my group is going to suggest that real victims ought not have access to the courts,” said McKinney, whose group consults with ALEC on drafting model bills. “But it seems to me we can’t afford to unleash a hungry mob of plaintiffs’ attorneys, bringing technically oriented, nitpicking types of lawsuits.”

But even in 2010 — before the law was passed — the Pacific Research Institute, a San Francisco think tank that advocates for tort reform, ranked Wisconsin the ninth best state in the nation for its “favorable business climate for tort liability.” States with the highest rankings had smaller plaintiff awards, smaller plaintiff settlements, fewer lawsuits or some combination of the three.

Wrongful death, personal injury and medical malpractice cases, which encompass many of the suits against nursing homes and other health care providers, decreased by about 28 percent in Wisconsin between 2000 and 2010, according to a review of court records by the Wisconsin Association for Justice, a trial lawyer group.

Reports crucial in lawsuits

In March 2010, before the tort reform bill was passed, Carol Lehman filed a lawsuit against KindredHearts, a Green Bay assisted living facility where her husband, Howard, lived.

In February 2008, Howard Lehman died from a brain hemorrhage after falling and hitting his head at KindredHearts – Green Bay, an assisted living facility. A state investigation later found that Lehman fell at KindredHearts more than 30 times over a 10-month period. Attorney Ann Jacobs said state investigation reports helped her trace a pattern of neglect at the facility. Photo courtesy of the Lehman family.

In February 2008, he fell at the facility, hit his head and died from a brain hemorrhage. A state investigation later found that he fell at KindredHearts more than 30 times over a 10-month period.

Following Lehman’s death, the state health department cited the facility for five violations, fined it $2,800 and ordered it not to admit any new residents until it completed a plan of correction, state records show.

In March 2012, Carol Lehman settled with KindredHearts, according to court records. Jacobs, the Milwaukee attorney who represented Lehman, said the case has been “concluded,” but declined to offer details. She said state investigation reports helped her build the case and trace a pattern of neglect at the facility.

Dane County Circuit Court Judge William Hanrahan, who prosecuted crimes against the elderly for 19 years as a district attorney and an assistant attorney general, said he is troubled by the law because it forbids district attorneys and the state Department of Justice from using these records as evidence in criminal cases.

“There are witness statements in state inspection reports. You can’t replace those,” Hanrahan said. “I can’t imagine if it were a homicide. It would be like saying the police reports couldn’t be used.”

DOJ spokeswoman Dana Brueck said the legislation makes it more difficult to prosecute facilities or staff that allegedly neglect or abuse residents. She said there may be “situations where we cannot intervene as early as we could before to avoid more serious neglect and abuse” in facilities.

Law’s effect still to be seen

Wisconsin’s tort reform bill owes much to ALEC, which creates model legislation that largely promotes pro-business, socially conservative policies, such as stricter immigration laws and relaxed environmental regulations.

The Madison-based Center for Media and Democracy, a left-leaning nonprofit that has researched ALEC and its policies, published an annotated copy of the Wisconsin bill online, drawing links to eight model ALEC bills.

And an analysis conducted by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism in collaboration with the Sunlight Foundation, a nonpartisan group in Washington, D.C., found that more than two dozen fragments of Wisconsin’s tort reform law match model ALEC bills verbatim.

U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan, D-Madison. Henry A. Koshollek/The Capital Times

That should make people nervous, said U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan, D-Madison, a former state legislator who has attended ALEC conferences and criticized the group.

“Bills drafted by ALEC are drafted by special interest groups and corporations,” Pocan said. “The people benefiting from the legislation are the ones who are creating it.”

ALEC spokesman Bill Meierling noted that most of the group’s members are state lawmakers — and that legislators customize ALEC bills to meet the needs of their constituents.

“It’s exciting that ALEC model legislation is having this impact,” Meierling said. “That’s really part and parcel of the American experience, to have citizen activism in government.”

Advocates of Wisconsin’s tort reform law say it’s still too early to gauge its effect. Like Walker, they see it as a step toward improving Wisconsin’s overall business climate.

“In some ways, we’re talking about job retention, not job creation,” said John Sauer, president and CEO of LeadingAge Wisconsin, an association of nonprofit nursing homes that testified in support of the bill. “Anything we can do to limit cost increases is going to protect jobs.”

Personal injury attorneys say that families of nursing home residents are already feeling the effects of the legislation. Several attorneys said they have turned down meritorious cases because the new law makes it harder and more costly to sue nursing homes and other health care facilities.

“Even before this legislation, these were very difficult, expensive, time-consuming cases,” said Jason Studinski, a Stevens Point attorney who specializes in elder abuse lawsuits. “Frankly, once a victim knows what hurdles are in their path, some choose to go away, even if they have a legitimate claim.”

Joshua Wahl, now 33, is slowly beginning to heal. After surgery, he spent nine months lying on his stomach at an Eau Claire hospital, receiving wound therapy for his bedsore. Now he’s at a nursing home in Clark County. At least twice each week, Nichols-Palmerton drives 70 miles to visit him.

“I beat myself up every day for this,” she said. “This shouldn’t have happened to him. No one should have a decent life taken away from them because of negligent care.”

Coming tomorrow: Nursing Homes Fail to Report Deaths, Injuries

What to do if you suspect neglect or abuse

If you think a loved one has been neglected or abused in a nursing home or assisted living facility:

- File a complaint with the Wisconsin Department of Health Services Division of Quality Assurance by calling 800-642-6552 or going to http://1.usa.gov/VJcMnu.

- Contact the Wisconsin Long Term Care ombudsman’s office at 800-815-0015.

- Document the full nature and extent of the resident’s injuries and any details about the suspected mistreatment or neglect. If possible, take photos.

- Ask for a complete set of the resident’s medical records.

- Ask for a copy of the incident report that the facility prepared after the accident or injury.

- If there’s a death involved, have a full discussion with the physician or medical examiner.

- Note the full names of all staff members you’ve spoken with regarding the resident’s care.

- Contact county-level Adults-at-Risk helplines. For a complete list, visit http://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/aps/.

How tort reform bill changed state law

Wisconsin Act 2 of 2011 changed state law regarding long-term health care providers in a number of ways. Here are some of them:

Certain records are inadmissible: State investigation records of nursing homes, and incident reports that facilities submit after a resident’s injury or death, are barred from being used in civil and criminal cases. These records are still available to the public. (See sidebar: How to find nursing home inspection reports.)

Caps on damages: In negligence and wrongful death lawsuits against long-term care providers, plaintiffs seeking non-economic damages, for such causes as pain and suffering, are limited to $750,000, the same limit already in place for medical malpractice cases. And punitive damages may not exceed $200,000. Previously, there was no cap on punitive damages or damages in negligence cases; damages for loss of society and companionship in wrongful death cases were capped at $500,000 per occurrence in the case of a deceased minor, or $350,000 per occurrence in the case of a deceased adult.

Higher bar for some damages: Plaintiffs seeking punitive damages must prove that a health care provider either intentionally caused injury or knew an action was “practically certain to result in injury.”

Two-for-one fines: If the state and federal government fine a nursing home for the same violation, the state fine is eliminated.

How to find nursing home inspection reports

In January, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services began publishing state inspection reports of nursing homes, assisted living facilities and other health care providers on its website. Records are available from July 2012 onward.

To access the reports, click here and select Provider Search. A user may search by facility name, location and type.

If the state found violations during an inspection, each report includes the severity level of the violation and a detailed narrative of events, often including statements from employees, residents and family members, notes from medical records and facility incident reports, and general observations made by the surveyor.

Inspection reports of federally certified nursing homes are also available online, from 2009 onward. The nonprofit investigative news organization ProPublica developed an interactive app to search this data, which it culls from the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Lastly, state inspection records are available at individual facilities. Federal and state law requires federally certified nursing homes as well as non-certified residential facilities to post its most recent inspection report in a lobby or other accessible area. Facilities are permitted to charge photocopying fees.

Reports older than July 2012 are available from the state Department of Health Services; contact the Division of Quality Assurance at 608-266-8481. The agency charges 25 cents per page in copying fees, and may also charge for searching for records, retrieving files from storage and copying photos, depending on the request. For example, the agency billed the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism $441 for 201 records from six nursing homes and assisted living facilities.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. This story was a produced in collaboration with Wisconsin Public Television.

All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

-

Wisconsin’s Medicaid Postpartum Protection Lags Most States

Feb 27th, 2024 by Rachel Hale

Feb 27th, 2024 by Rachel Hale

-

Wisconsin Has A “Smart Growth” Law To Encourage Housing, But No One Is Enforcing It

Dec 22nd, 2023 by Jonmaesha Beltran

Dec 22nd, 2023 by Jonmaesha Beltran

-

Milwaukee County Is Funding Affordable Housing In Suburbs

Dec 21st, 2023 by Jonmaesha Beltran

Dec 21st, 2023 by Jonmaesha Beltran

A terrifically well written piece. The supporting information, resource information and video make this article stand out and reflect high quality work.

The subject matter adds another chapter to the twisted logic of the Walker administration. He continues to steer Wisconsin on a high-speed race to the bottom.