A City of Theaters

Since the 19th century’s German language playhouses, the city has built and renovated countless facilities for theater.

From watching shows from my Dad’s light booth as a kid, to being directed by the incomparable, unconquerable Barbara Gensler at Shorewood High School, to acting and directing in my own right at college, theater has been a near constant in my life. So I have a bit of a bias when it comes to not only theater, but also theaters. Personally, I find few moments more exciting than the slow dim of the house lights, nor experiences more intimate than the connection between performer and audience. Like our ancestors sitting around the fire, enveloped by night and listening intently to a storyteller, we are transported by theater, however briefly, from our world to inhabit another. Today the night and the fire are artificial, yet the echoes of those early days where the gods brought the rain and spirits inhabited the trees are unmistakable.

Although the physical presence of Milwaukee’s early theatrical traditions has largely disappeared, Ward Memorial Hall (5000 W. National Ave., built 1881) provides a glimpse into those heady times. Part of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (Milwaukee Soldier’s Home for short) the facility was established in 1867 through combined federal and local efforts. The Soldiers Home was one of three original “Asylums for Disabled Veteran Soldiers” created by the US Congress in 1865 to provide care and rest for wounded veterans of the Civil War. Architecturally Ward Memorial Hall falls most comfortably into the catchall “Victorian” label. The cream city brick building makes use of red brick accents (“polychrome” to use the technical term), which is reminiscent of the Venetian Gothic Revival promoted by English thinker John Ruskin that was very popular at the time. With gothic architecture, however, you would expect the arches above the windows to come to a point, not rounded like they are here. At the same time the floral capitols of the veranda feel a little closer to gothic revival, so while it is somewhat atypical, I would still slip it into that camp. The building has not been occupied for some time and while the VA (who own the entire historic site) have done work on the roof and veranda the structure is still in desperate need of restoration and preservation (see an additional gallery of Ward Memorial Hall here), as is much of the historic district.

Ward Memorial Hall

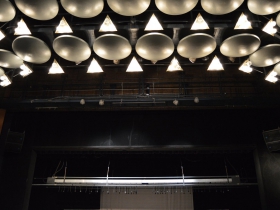

Our second theater is also a cream brick structure; however it began life as something very different. The Wayne and Kristine Lueders Opera Center (926-930 E. Burleigh St., built early 1900’s) is the home of the Florentine Opera Company. Now a multi-purpose space, the warehouses were at various times owned by church contractors, an Asian importer, and the La Lune Furniture Company, the founders of which (Mario and Cathy Costantini) played an important role in the opera center’s realization. The center has workshops for costumes, wigs and scenery as well as a library and rehearsal spaces, the largest of which can be converted into a black box theater that can seat a little fewer than 100 people. Black box theaters are what their name suggests: small, unadorned spaces often with black walls used for intimate, smaller scale productions.

Wayne and Kristine Lueders Opera Center

Like the Florentine Opera Center many of the city’s performance spaces are the result (at least in part) of ambitious renovations and conversions of older buildings. The Broadway Theatre Center (158 N. Broadway, 1907, 1993) is a stunning example of just such a conversion. Originally a warehouse for the O.R. Pieper Company, in 1993 the building, which fits into a kind of commercial vernacular style, was converted into office and fabrication space for the new Cabot Theatre, built on vacant land south of the warehouse at the intersection of Broadway and E. Menomonee St. The Cabot has a capacity of 358 and is a stunning reproduction of a Baroque European opera house with a proscenium (the arch over the stage that separates it from the house) and fly loft for hoisting and lowering backdrops and scenery. The painted detailing is exquisite, but of particular note is the ceiling mural, which has been painted to give the illusion of a dome and is adorned with personifications of the Nine Muses and a Milwaukee skyline. The theater’s exterior has a number of postmodern touches that seek to match its older neighbors, specifically, thick brick piers that run up the façade, a common feature throughout the Third Ward. Salvaged terra cotta lion-heads were also incorporated into these piers, giving it a bit of ornamentation that is also in keeping with the historic nature of the neighborhood.

Broadway Theatre Center

The second converted space is the Alchemist Theatre (2569 S. Kinnickinnic Ave., built most likely in the 1920’s). The building is one of the many mixed-use Mediterranean Revival buildings built throughout Milwaukee during the early 20th century and has at various points been everything from a copy store to a record shop. In 2007 the Alchemist moved in and converted the space into a charming, intimate studio theater with a capacity of 68. Studio theaters are typically smaller spaces with more flexible set ups that often lack the more elaborate technical equipment of proscenium theaters like the Cabot.

Alchemist Theatre

Both the Cabot and the Alchemist are examples of conversions from non-performance venues, while the Helen Zelazo Center for the Performing Arts (2419 E. Kenwood Blvd.) is a space that embraces its original use. Completed in 1922 the center was originally the Temple for Congregation Emanu-El B’ne Jeshurun, the fusion of Milwaukee’s two Reform congregations. The limestone building is among Milwaukee’s best examples of neoclassical architecture and features an impressive set of stained glass windows depicting, among other things, seven-branched menorahs, a Shabbat dinner, and broken chains. Today the 758-seat concert hall is used mostly for musical concerts, however it is occasionally used for theatrical performances and, fittingly, worship services.

Helen Zelazo Center for the Performing Arts

Academic institutions are responsible for many of the city’s theatrical spaces and performances, and the Thomas Edward Wildrick Theater at the Milwaukee High School of the Arts (2300 W. Highland Ave.) is one of several active theaters built by the Milwaukee Public School System. Originally West Division High School, the present building was finished in 1958 after more than a decade of wrangling for a new facility. The high school is an example of postwar or midcentury modernism, notable for its horizontal banded windows, flat roofs, and chrome highlights. The theater, which has a capacity of 901, has several truly endearing details including multicolored acoustical tiles that adorn the walls and the seats, which not only continue the chrome highlight aesthetic but also feature some amazing, streamline moderne style brackets and aisle lights.

Thomas Edward Wildrick Theater

Moving back to university theaters, Marquette University’s Evan P. and Marion Helfaer Theatre (525 N. 13th St., 1975) is an example of what is probably early postmodernism. The theater eschews the rectilinear forms of international style modernism in favor of sharp angles, pronounced asymmetry and decorative elements, all features of postmodern design. The dark brick, stark angles, monumentality and prow-like entrances actually remind me a bit of early 20th century Expressionism and the Chilehaus building in Hamburg in particular. The theater itself is modest in size with some surprisingly interesting brickwork and striking round ceiling acoustical tiles.

Evan P. and Marion Helfaer Theatre

The Northern Lights Theater at the Potawatomi Hotel & Casino in the Menomonee River Valley (1721 W. Canal St., built 2000, renovated 2010) is another postmodern Milwaukee theater. The theater, which can hold around 500, is unique on this list for its table and booth seating, which give the space a more intimate, cabaret feel distinct from a traditional, completely darkened theater. Like the casino itself the theater draws on Native American imagery and aesthetics, in this case painted beadwork and floral reliefs used to wonderful effect to create the proscenium. In an nice bit of serendipity the Northern Lights’ pre-renovation seats are now at the Alchemist Theatre, while the La Lune Furniture Company, which shares the building with the Florentine Opera, provided a great deal of the casino’s furniture.

Northern Lights Theater

Another theater that embraces motifs associated with its owners is the Divine Savior Holy Angles High School’s Robert and Marie Hansen Family Fine Arts Theatre (4257 N. 100th St., built 2003). Among Milwaukee’s newest performing arts spaces (it seats 752), it is another example of a proscenium theater with a fly loft and scene shop. One nice touch is the art deco crowns over the theater’s main entrances, which are references to the original building’s overall architectural style. Inside there is a notable cross motif that embraces the back and side walls, befitting the school’s Catholic identity. Indeed, the theater can and is often used for worship services during which a cross can be lowered from the rafters.

Robert and Marie Hansen Family Fine Arts Theatre

The final theater I wish to discuss is also very new and another example of a clever conversion of a non-theatrical space. Next Act Theatre (255 S. Water St.) is a 152-seat performing arts facility created in 2012 from what was the old Transpak Crane Bay building. The theater is very open and flexible with bleacher style seating that can be easily reconfigured to fit the needs of the production. Overall the space at Next Act is Spartan with simple elevated platforms acting as the stage, in this case arranged into a thrust configuration. While not richly adorned like the Cabot or Zelazo theaters, Next Act nicely illustrates that the true substance of theatrical spaces is found not in their design but rather how they are used. It’s ironic that these buildings, among our most monumental and enduring, become so much empty space when deprived of the very ephemeral moments and performances for which they were built. Whether the theater is a proscenium or black box, studio or cabaret, it is the interplay between performer and audience that gives these places meaning.

Next Act Theatre

So I implore you friends, go forth and see some theater, and let the affectionate wind of your applause fill their sails.

Special thanks to Elizabeth Hummitzsch and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Bill Florescu, Richard Clark and the Florentine Opera Company, Jennifer Samuelson and the Skylight Opera Theater Company, Aaron Kopec and the Alchemist Theatre, Randall G. Tumbull Holper and UWM, Tony Tagliavia and MPS, Stephen Hudson-Mairet, Kevin Wleklinski and Marquette University, Corri Hess and Potawatomi Hotel & Casino, Michael Stoddard and DSHA, and finally David Cecsarini and Next Act Theatre.

Milwaukee Architecture

-

10 Examples of The Classical Style

May 3rd, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

May 3rd, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

-

The Rise of Suburban Style Homes

Mar 12th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

Mar 12th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

-

The First 100 Years of City Homes

Feb 25th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

Feb 25th, 2015 by Christopher Hillard

This is where we should be putting more money instead of a basketball team that plays here 50 times or so in the year.

The Pabst Theatre was built on the site of the Nunnemacher Grand Opera House which opened about 1872. Frederick Pabst had purchased the Grand Opera House about 1890 and renamed it the Stadt; when it burned in January 1895, he ordered it rebuilt. The Pabst opened November 9, 1895. This means that this site has the longest history of being dedicated to the performing arts in Milwaukee.

@Konrad It’s a good point. Theaters were among the most susceptible buildings when it came to fire (the Iroquois Theater in Chicago, which burned down just three years after the Pabst opened, is a particularly bleak example). In some ways it makes the continued existence of Ward Memorial Hall, which would have employed gas footlights and was built well before modern fire codes, all the more extraordinary.

Sorry, that should have read “eight years”. The Iroquois burned down in 1903.