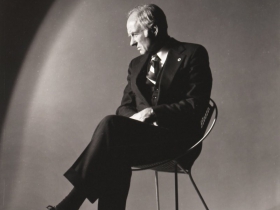

The Maximal Minimalist

Tom Bamberger is an artist given to extremes, as landmark MOWA show proves.

It is fitting that Tom Bamberger: Hyperphotographic is the first exhibition to engulf all three of the Museum of Wisconsin Art’s changing exhibition spaces (three galleries, two hallways and an atrium, to be precise). As the size, subject matter and technical achievement of the 130+ photographs and digital works on display make evident, Tom Bamberger is an artist given to extremes. (Urban Milwaukee readers will also know Bamberger from his In Public column on architecture and public art.)

The most self-evidently extreme of Bamberger’s works are two monumental photographs taken with a GigaPan, the camera co-invented by NASA to capture extremely high-definition pictures of the surface of Mars. Bamberger puts the technology to different use. To be sure, a compulsion to saturate his photographs with as much detail as possible – to “take up your brain’s bandwidth,” in his apt phrase – is one of the guiding threads of Bamberger’s oeuvre. But the GigaPans contain more than detail. As their curatorial classification “Timescapes” suggests, Bamberger’s GigaPans are photographs of time. Indeed, the thirty-five feet of Civil Twilight and twenty-two feet of Pete’s World each embrace roughly thirty-five minutes.

How is it possible to compress duration into a moment? As noted, the GigaPan was invented to take detailed panoramic photographs. Such scientifically useful muscularity of detail requires time to gather. To do so, the GigaPan is programmed to divide a vista into a composite of hundreds of individual photographs, which it then takes one by one, top to bottom, left to right (or vice versa). Consequently, successive rows of images may be recorded minutes apart.

Bamberger took advantage of this technical quirk. Civil Twilight, for instance, is a study of the eponymous time when the sun first drops below the horizon. Weighing in at some three hundred photographic cells, the thirty-five-foot long photograph rewards being viewed from different distances – up close so as to appreciate the density of detail and from afar for the panoptic view.

Despite the enormity of his “Timescapes,” Bamberger is really a minimalist at heart. Other bodies of work operate on a significantly smaller scale, distilling photography to its most basic elements and creating a photographic analogue to literary forms like the haiku or aphorism.

For years Bamberger was fixated on horizon lines, using the phenomenon to orient his photographs. The images themselves are rather small and their compactness is enhanced by being printed on outsized sheets of unexposed white paper. “The small horizons have the same density of information as larger photographs,” notes Bamberger, “the difference is in the appropriate viewing distance.” Just as a shout might arouse us from distraction whereas a whisper bids us listen carefully, the small horizons draw us closer as if ready to divulge a secret.

The “Horizon Line” photographs, on the other hand, are comparatively placeless. Differentiating marks have been removed by design and often the only clue situating the subject is in the title, as in the case of Untitled (Pretty Wisconsin Landscape) and Untitled (East Colorado). The grammar of this suite of photographs is comprised of rich tonal and textural contrast between the earth and the bleached-out skies, which blend imperceptibly into the white of the photographic paper.

Bamberger sees the “Horizon Line” photographs as his conquering of the need for meaning in art. After his early forays in portraiture and landscape photography, which are psychologically and symbolically suggestive, Bamberger became skeptical of the place of meaning in art. Photographically, this skepticism manifested in moving farther and farther away from his subject matter, progressively denuding his pictures of human figures and distinctive markers of place. Bamberger’s horizon line photographs are his first to fully realize the potential of placeless places.

Ok, a multi-image digital installation nearly ten years in the making, is Bamberger’s return to meaning. The setup replicates Bamberger’s personal desktop computer, for the simple reason that Ok is a refined version of Bamberger’s screensaver. As an image connoisseur, whenever a photograph caught his eye or a digital experimentation yielded a satisfying result, Bamberger would save it to a folder entitled “Ok.” When his screensaver kicked on, images would be drawn randomly from this cache of approximately eight thousand, appearing on one of three screens at skewed intervals of eight seconds.

What initially interested Bamberger in the artistic potential of his screensaver was not merely the fact that he was no longer the center of attention whenever his computer took a nap, but the curious response that was common across viewers: “No matter whether they’re art historians or the Fed Ex guy,” says Bamberger, “there’s a sound people make when they watch it—‘hm.’ It’s the sound of something making sense but not in any linear way.” That the effect of Ok was the same for the artistically literate and laymen suggested that something deeper was at play, something about the sense-making faculties of the human brain.

Recently, Bamberger sent me an email with the slightly alarming subject line “IMPORTANT READ ME INTERESTING.” The email linked to a recent piece by Teju Cole, the photography critic of The New York Times Magazine, entitled “A Photograph Never Stands Alone.” The email consisted entirely of a lengthy quote culled from the article and, despite offering no commentary, it was clear from our many conversations that he was thinking of Ok: “…soon after the invention of photography, the world was full of photographs, and newly made photographs could not avoid semantic contamination…All images, regardless of the date of their creation, exist simultaneously and are pressed into service to help us make sense of other images. This suggests a possible approach to photography criticism: a river of interconnected images wordlessly but fluently commenting on one another.”

Ok makes a photography critic of the viewer. The aforementioned “hm.” that caught Bamberger’s attention is simply the viewer’s recognition of interconnections between the images; for instance, when a triptych of tree limbs, masts in a shipyard and branching fractions line up like a slot machine that has just hit the jackpot.

Tom Bamberger: Hyperphotographic is the artist’s most complete retrospective to date, encompassing his earliest photographic experiments from the late 1970s through digital works completed this year. Despite the diversity of subjects covered and techniques used, the retrospective reveals abiding artistic impulses that have guided Bamberger’s work over the past 40 years. For instance, from his early adoption of Kodak’s SO424, a film used by scientists and military personnel to record lasers, to more recent work with the GigaPan, Bamberger’s interest in science and technology has informed his practice from the start.

The retrospective was occasioned by Bamberger’s gift of nearly 400 works to the Museum of Wisconsin Art. “This is the largest and most important gift of artwork to MOWA since its founding in 1961,” says Laurie Winters, the CEO and Executive Director of MOWA. The retrospective is a rare opportunity to see a lifetime of work emanating from one of Wisconsin’s boldest and most distinctive artistic visions.

Tom Bamberger: Hyperphotographic is on view at the Museum of Wisconsin Art through May 21. On April 8 and 22, from 1-4 pm, Bamberger will be at MOWA to speak with visitors.

On Saturday, May 6, at 1 p.m., Bamberger will be joined by friends and colleagues including Debra Brehmer, Director, Portrait Society Gallery; Dick Blau, Photographer and Professor of Film Emeritus at UW-Milwaukee; John Koethe, Distinguished Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at UW-Milwaukee and Wisconsin’s first Poet Laureate; Dean Sobel, Director, Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, Fred Stonehouse, Professor of Painting at UW-Madison; and Laurie Winters, CEO and Executive Director of MOWA.

On May 13, there will be a discussion on “Placemaking in Milwaukee” with Bamberger and a slew of local architects and leaders in Milwaukee’s creative community. For more information on these and other MOWA events, see wisconsinart.org.

Tom Bamberger: Hyperphotographic Gallery

Art

-

Exhibit Tells Story of Vietnam War Resistors in the Military

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

Mar 29th, 2024 by Bill Christofferson

-

See Art Museum’s New Exhibit, ‘Portrait of the Collector’

Sep 28th, 2023 by Sophie Bolich

Sep 28th, 2023 by Sophie Bolich

-

100 Years Of Memorable Photography

Sep 18th, 2023 by Rose Balistreri

Sep 18th, 2023 by Rose Balistreri

Kudos to Tom for scoring such an important and prestigious exhibit. I have yet to see it but am anxious to do so.

I was struck by Friedman’s observation “That the effect of Ok was the same for the artistically literate and laymen suggested that something deeper was at play, something about the sense-making faculties of the human brain.” From my personal experience, I believe John Cage pointed this out many times through various examples a long time ago. Viewers/auditors just have to pay attention to their own response/reactions to stimuli, natural or human-made, to discover this.

I’m sure other artists have as well. Not to mention thinkers like Carl G. Young et al.

Glad to know Tom is practicing in the mainstream.

Have to see this show!