What Makes a Great Conductor?

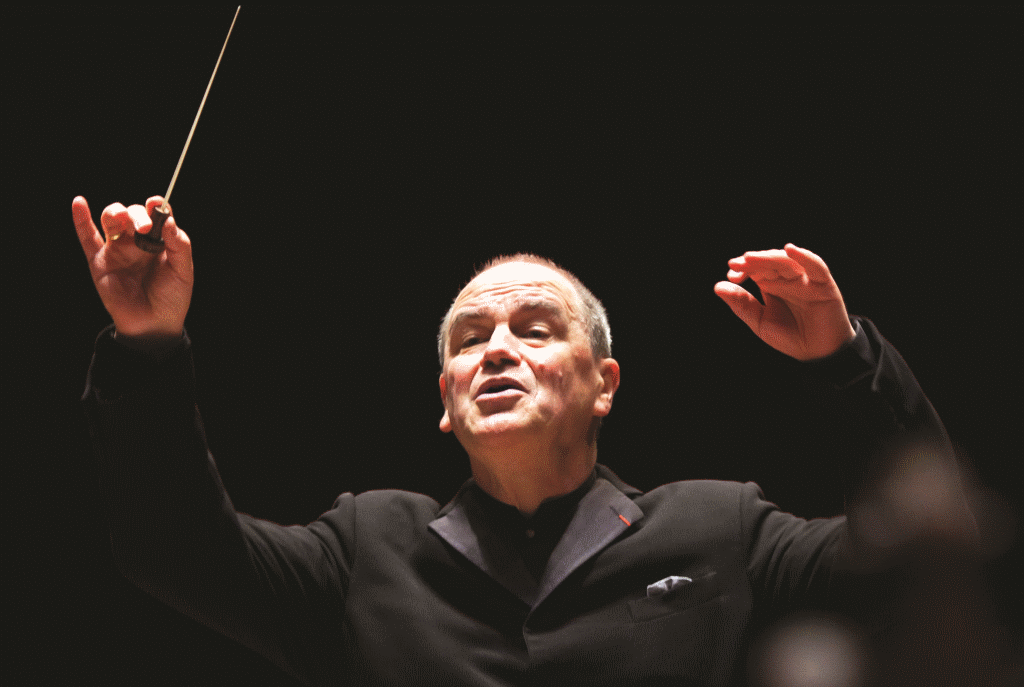

MSO guest conductor Hans Graf nailed that question, and pianist Orli Shaham thrilled.

It was difficult not to play the game of “what if” while enjoying the return of Hans Graf for another stint as guest conductor with the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra this past weekend. Graf was a musician favorite two decades ago when the MSO was casting about for a music director to replace Zdeněk Mácal, and it was delightful to see him back. Graf’s hand gestures are crystal clear, he stays still on the podium, and as an interpreter, he is an insightful musician. It is remarkable just how many conductors cannot relay a clear beat pattern and give precise, well-timed cues. Graf takes all the guesswork out of his job as timekeeper, which gives the musicians in the orchestra the confidence to look up. Being still on the podium—which may seem odd to some as a desirable quality—means the leaps and gyrations some conductors can’t resist aren’t present and therefore don’t distract from the performers’ or listeners’ experience. Most importantly, he thoughtfully crafts the overall architecture of each work while giving free room for expression to individual solo passages in the orchestra. On Saturday night, in a program of richly varied musical ideas, Graf’s many strengths produced glorious results.

Not alone in his artistry, guest pianist Orli Shaham played the spots off Béla Bartók’s Concerto No. 3 for Piano and Orchestra. Shaham plays with power and fluidity, and she seems marvelously committed to creating a chamber music experience from her bench at the keyboard. Often angled toward the conductor or the orchestra, Shaham was dialed in to the whole score, not just the mammoth undertaking of Bartók’s challenging piano part. Bartók, one of the giants of twentieth-century music, gave the world perhaps his most accessible large-scale work in this concerto. The harmonies and form are easily digestible, and Shaham made the piece seem both intimate and thrilling. Her chords in the opening of the second movement rang with evenly voiced dynamics to cast a spell of stirring profundity, and birdsongs from the woodwind section dappled the music. The third movement was rhythmically vigorous, and Shaham made good use of her scorching technical gifts.

The program opened with the darkly atmospheric Musique funèbre by Witold Lutosławski. This eerie piece for two string orchestras created a pastiche of tritones, death knells, haunting pizzicatos with shimmering tremolo accents, jazzy syncopated outbursts, and tone clusters that resolved into stark unison melodies. Graf paced the Lutosławski for maximal dramatic effect, and the playing of cellists Scott Tisdel and Peter Szczepanek and violists Robert Levine and Nicole Sutterfield was extremely satisfying. Tisdel’s luxurious tone and hair-raising decrescendo down to nothing was particularly gripping. Lutosławski’s work is worthy of several hearings. There’s a lot of magic and mystery lurking in those bars. A delightfully haunting work.

The second half of the program was devoted to Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6 in B Minor, Op. 74, “Pathétique.” Graf’s tempos kept this warhorse moving, never succumbing to lugubriousness or caricature. The first movement, opening solemnly with a melancholic bassoon solo, shifted abruptly to brass fanfares, florid woodwind passages, and fiery string lines. The Allegro con grazia, a light waltz in an unusual 5/4 time signature, was elegantly played. The brisk Allegro molto vivace featured tight ensemble from all quarters as the music marched triumphantly to the end of the movement. As though the evening weren’t good enough already, a miracle worth mentioning transpired: Not a soul clapped between the rousing third movement and the fourth, keeping the air clear for the aching suspensions of the Finale: Adagio lamentoso, which, when played so well, became a tear-jerking surprise. There was a spate of particularly fine playing from clarinetist Todd Levy, flutist Sonora Slocum, bassoonist Rudi Heinrich, bass trombonist John Thevenet, tubist Randall Montgomery, and timpanist Dean Borghesani. Some wonderfully raucous and buzzy stop-muted playing emanated from hornists Dietrich Hemann and Joshua Phillips, and the string section was rich and facile. The whole orchestra sounded marvelous under Graf’s influence.

Review

-

‘L’Appartement’ Is a Mind-Bending Comedy

Mar 25th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

Mar 25th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

-

Highlands Café Is Easy to Love

Mar 15th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

Mar 15th, 2024 by Cari Taylor-Carlson

-

‘The Mountaintop’ Offers Very Human Martin Luther King Jr.

Mar 11th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth

Mar 11th, 2024 by Dominique Paul Noth