Army Facility Still Pollutes

Badger Army Ammunition Plant left stew of chemicals that pollute groundwater.

Soil and groundwater polluted

In 1977, the same year that Koch and her husband built their house, the Army began to assess the environmental damage at Badger. It started looking at treatment options for cleaning up the contamination found in multiple areas at the site, where for three decades the military had burned excess chemicals and waste in open pits.

A soil vapor extraction system was installed to remove chemicals in waste pits. Some 1,600 pounds of volatile organic compounds were removed, and 2,280 cubic yards of soil were dug up, moved off site and incinerated.

Once the vapor removal system was discontinued in 1999, a bio-treatment system was installed in one of the numerous waste pits areas. Groundwater was extracted from under the pit, treated with phosphate and re-injected into the soil.

A pair of reservoirs on the northern end of the Badger Army Ammunition Plant once provided water for the 7,000-plus acre weapons manufacturing facility. Although the pumping system has been disabled, the pools still hold water. Pictured near the facility during a tour of the grounds in 2012 are Sauk County Supervisor Donna Stehling, left, and Joan Kenney, former Badger Army Ammunition Plant commander’s representative. Photo by John Hart of the Wisconsin State Journal.

At another site, chemicals were burned along with trash, construction rubble and coal ash from the power plant at Badger. About 4,260 cubic yards were excavated from that area and incinerated off-site.

Yet, even with this elaborate treatment system in place, highly dangerous compounds including dinitrotoluene (DNT), carbon tetrachloride and trichloroethylene (TCE) made their way into the groundwater.

In fact, since well monitoring began at Badger in the early 1980s, varying levels of these three chemicals have been detected in groundwater at the site and in private wells south and southeast of the site.

Environmental data produced for the Army in 2011 showed that levels of DNT, which can affect the central nervous system and blood; carbon tetrachloride, a probable human carcinogen; and TCE, a known carcinogen with a wide array of other harmful health effects, have diminished over time.

However, the latest environmental monitoring data from November 2014 found that levels of all three contaminants continue to exceed Wisconsin groundwater enforcement standards in a number of wells on or near the Badger site.

Will Myers, the DNR’s team leader for environmental remediation at Badger, was asked what might cause such high levels after 25 years of cleanup.

An aerial view looking east shows the grounds of the Badger Army Ammunition Plant near Baraboo in 2012. The Army continues to clean up groundwater pollution left by the now-defunct manufacturing plant and has proposed building a drinking water system for about 400 nearby homes whose wells are tainted or at risk of contamination. Photo by John Hart of the Wisconsin State Journal.

Myers said “evaluating contaminated groundwater can be difficult” because contaminant levels can “fluctuate for many reasons” since groundwater is a “very dynamic system.” Changing elevation levels and flows can cause “spikes” in contaminant levels, he said.

Studies refute cancer concerns

Residents living near Badger have long been concerned about the cancer risks associated with exposure to contaminated groundwater used for drinking.

In response to those concerns, state health officials conducted a cancer rate review in 1990 of the communities near Badger. It concluded that between 1980 and 1988, residents did not experience “statistically higher than expected” cancer deaths in areas where contaminants were detected in private wells.

The study also looked at cancer mortality rates between 1960 and 1988. That survey for 11 types of cancer concluded residents living near Badger had cancer mortality rates similar to rates of residents in other parts of the state.

A follow-up study conducted in 1997 concluded that cancer mortality and incident rates for residents near Badger were still similar to other Wisconsin communities.

“The problem with some of the wells they’ve been testing is there will be three different chemicals that were found. … Some of them have two to three chemicals but not at levels (higher than the state enforcement standards) so they don’t think it’s a problem. No one can give us an answer as to what kind of chemical cocktail that’s making.”

Myers, in response to questions posed by Citizens for Safe Water Around Badger, said residents need not be concerned. The environmental nonprofit, based in Merrimac, has pushed for monitoring and remediation at the site for years.

“For both soil and groundwater at Badger, the concentrations are low, there is very limited interaction between compounds, and the standards are very conservative,” Myers wrote.

But state epidemiologist Dr. Henry Anderson said there is uncertainty — and no health standards — regarding the cumulative effect of multiple chemicals in the groundwater.

Koch has known a number of families living near Badger that have been affected by cancer. It is this anecdotal evidence that connects the dots for her.

Breakdown products

Laura Olah, executive director of Citizens for Safe Water Around Badger, also has asked regulators to set health advisory levels for products that result from the breakdown of the explosive compound DNT, 16 of which have been detected in the groundwater at Badger. Olah said some of the products can be more harmful than the original contaminant.

Olah is also concerned that additives such as 1,4-dioxane, a compound used to stabilize TCE, are not being monitored at the site. The DNR has said it does not monitor for the compound. The EPA found after a multi-year scientific review of the health risks that 1,4-dioxane “can cause cancer or increase the incidence of cancer when people are exposed to relatively low levels for extended periods of time.”

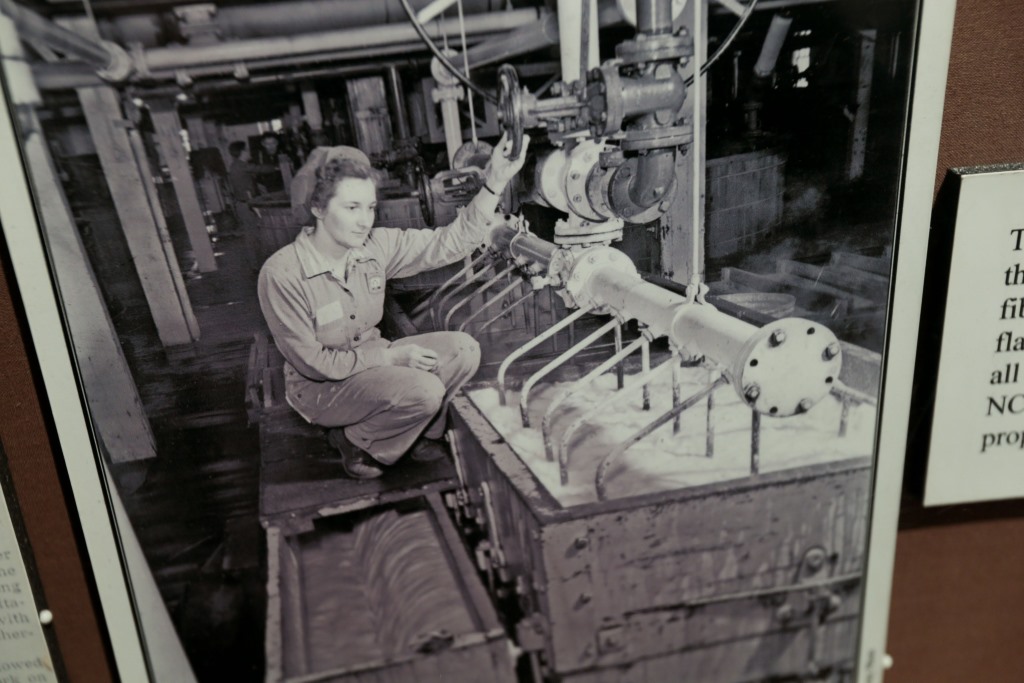

A photo on display at the Museum of Badger Army Ammunition shows a woman working with nitrocotton slurry at the facility. Decades of ammunitions manufacturing at the plant left a legacy of polluted groundwater. The Army has been cleaning up the aquifer and soil for years and has proposed spending an estimated $40 million to provide a source of clean drinking water to about 400 area homes. Photo by M.P. King of the Wisconsin State Journal.

Said Olah: “WDNR reports that the Army has not monitored groundwater for 1,4-dioxane, so there is no data to show whether or not it is present here. This is surprising given it is a probable carcinogen that is mobile in the environment and has not been shown to readily biodegrade.”

Tainted Water

-

Fecal Microbes In 60% of Sampled Wells

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

Jun 12th, 2017 by Coburn Dukehart

-

State’s Failures On Lead Pipes

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Jan 15th, 2017 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

-

Lax Rules Expose Kids To Lead-Tainted Water

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Dec 19th, 2016 by Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

It’s interesting that the military, paid for by us, is now claiming to install a solution to what they did, to be paid for … wait for it … by us! Why wouldn’t the powers that made the initial poisoning decision be responsible and accountable for the bill?

Operations of this facility predate most environmental laws and more scientific awareness that evolved in the 1970s. Even though as a society we still struggle with corporations still doing their best to buy off politicians that still want to turn a blind eye and mind to damages left on the landscape for hundreds or more years doing untold harm to humans and all other life forms. Once groundwater is damaged in this way it is near impossible to clean up.

Even though there were few environmental laws at this time, it was insanity dumping toxic materials all over the landscape. It really is inexcusable. It is immoral that business walks away and citizens are left holding the costly cleanup and harm to life.