The History of Kilbourn Avenue

Formerly Biddle and Cedar Streets, it was renamed and widened into grand civic lane.

Kilbourn Avenue, which has some of the city’s most beautifully landscaped medians, was not always wide enough for them and was actually not always called Kilbourn Avenue. The building of a bridge over the Milwaukee River resulted in the wide street with a new name.

When Solomon Juneau and Morgan Martin laid out Juneautown in 1835, Wisconsin was part of the Michigan Territory. The pair named several Juneautown streets for influential Michigan men, including John Biddle. Biddle Street, now East Kilbourn Avenue, ran from the lake bluff to the river. Biddle, who had served as Indian affairs agent at Green Bay and mayor of Detroit, was president of Michigan’s Constitutional Convention at the time the street was named for him.

On the other side of the river was Cedar Street, which originally extended west to N. 12th Street. Other Kilbourntown streets were also named for trees, including Chestnut, Sycamore, Tamarack, Poplar, Cherry and Walnut.

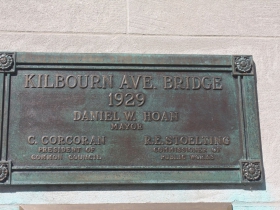

In the mid-1920s, the sentiment of the Common Council was to approve the bridge connecting the streets, but not the construction of the wide roadway. However, the city’s Socialist aldermen would not vote for the bridge without the commitment to widen the street. The Socialists prevailed and both the new bridge and road-widening projects were approved.

In 1929 the bridge was completed, the road was widened, and the two streets became one. Under a city policy put into effect a few years earlier, a street could only have one name, so something had to change. The residents on Biddle Street wanted Cedar renamed Biddle. The people on Cedar Street wanted Biddle to be called Cedar. Others did not want either Cedar or Biddle; they wanted a new name.

The Milwaukee Sentinel called for its readers to send in their suggestions and about 200 names were offered for consideration. Some wanted to honor one of three presidents: Lincoln, Coolidge or Hoover. Others offered the names of politicians closer to home, LaFollette and Hoan. Putting them all together, someone proposed that it be called Political Drive. Many submissions included the Civic Center aspect; among them were Civic Drive, Civic View Drive, and Civic Center Boulevard. The Common Council’s Streets and Alleys Committee sifted through the naming ideas and recommended that Kilbourn Avenue be chosen. The council agreed.

Byron Kilbourn, one of the founders of Milwaukee, was born in Connecticut in 1801. In 1834 Kilbourn, a civil engineer searching for a site for a port city on the western shores of Lake Michigan, decided that Milwaukee’s bay would be the best place. After buying land downtown west of the Milwaukee River, he set about turning Kilbourntown into a city. He replaced trees and marshes with streets and sidewalks. Over the years he helped improve access to the city with bridges, roads, railroads, and enhanced harbor facilities, in the process becoming a wealthy man. For 34 years Kilbourn promoted his city, which was combined with Juneautown and Walker’s Point to become Milwaukee in 1846. In 1868 he moved south for his health and died in Florida two years later.

Today a tour down Kilbourn Avenue from Juneau Park includes numerous opportunities to sit and cool off on a hot day. In addition to Cathedral Square, Red Arrow and Père Marquette parks, there are shady benches on medians, and at the plazas of MGIC, Plaza East, and the Peck Pavilion. Along the way are gardens, sculptures, attractive buildings and historical markers.

At Cass Street is the Woman’s Club of Wisconsin, built in 1888, and a city landmark. The building is a “gathering place for thoughtful and socially conscious women,” according to the organization’s website. It is the oldest woman’s club in the United States.

The rescue of Joshua Glover took place at the county jail that was at the north end of Cathedral Square in 1854. Glover, a black man who escaped slavery in Missouri, was captured in Racine and brought to the Milwaukee jail to await his return to Missouri as required by the Fugitive Slave Act. Milwaukeeans defied the law and broke Glover out of jail and sent him on his way to freedom in Canada.

During the summer, the thoroughfare along Cathedral Square Park is one of the most often closed streets in the city. It is blocked off on Thursday evenings for “Jazz in the Park” and on Saturday mornings for the farmers’ market. During Bastille Days, no traffic is allowed on the avenue between North Van Buren Street and North Broadway. But partying on the street appears to be doomed. The new streetcar line is slated to run on that section of the boulevard, requiring that the street remain open.

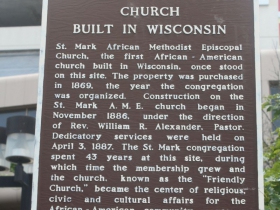

On West Kilbourn, a marker at N. 4th Street shows the place where the first African-American church built in Wisconsin was located. The Methodist Episcopal place of worship became known as “the friendly church” during its 43 years (about 1870-1913) at the site. Across the boulevard, between N. 4th and N. 6th Streets, the UW-Milwaukee Panther Arena and the Milwaukee Theatre flank the wide street, the latter originally known as the Milwaukee Auditorium, which was designed by Clas and opened in 1909.

Until the 1960s, West Kilbourn Avenue was a wide street all the way to the courthouse at N. 9th Street. Then, new freeway tunnels and a parking garage were constructed, cutting off Kilbourn Avenue at N. 6th Street and replacing the tree-lined boulevard with the inaccessible and desolate MacArthur Square. The street resumes on the other side of I-43 where it is too narrow for landscaped medians and becomes mostly residential. It ends at N. 38th Street.

Carl Baehr, a Milwaukee native, is the author of Milwaukee Streets: the Stories Behind their Names, and articles on local history topics. He has done extensive research on the sinking of the steamship Lady Elgin, the Newhall House Fire, and the Third Ward Fire for his upcoming book, “Dreams and Disasters: A History of the Irish in Milwaukee.” Baehr, a professional genealogist and historical researcher, gives talks on these subjects and on researching Catholic sacramental records. He earned an MLIS from the UW-Milwaukee School of Information Studies.

Sites Along Kilbourn Avenue

City Streets

-

The Curious History of Cathedral Square

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

Sep 7th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

Gordon Place is Rich with Milwaukee History

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

May 25th, 2021 by Carl Baehr

-

11 Short Streets With Curious Names

Nov 17th, 2020 by Carl Baehr

Nov 17th, 2020 by Carl Baehr

Could you do a history of Wisconsin Avenue next. It would be really interesting and helpful. Thanks!

In the future, Kilbourn Avenue ideally would serve as a parkway and pedestrian/bicycle connector. Imagine a green parkspace linking the courthouse, the riverfront, Cathedral Park, and Juneau Park…

East of the river, motorized vehicles could be shifted underground for 3-4 blocks. Ground level Kilbourn Avenue becomes Kilbourn Park, a wide greenspace connecting Juneau and Cathedral Parks. Underground, cars pass through with extra parking space and possibly gathering space as well. Between underground and on-ground, the area could host year-round food trucks or other pop-up retail.

The design of the Michigan Ave/Lincoln Memorial Drive/Couture bridgeway could inform the design of a new bike and pedestrian pathway leading from Lincoln Memorial Drive up to Juneau Park.

West of the river the sprawl of concrete could be greened up some, although it would make more sense to push bike and pedestrian traffic northwest through the new arena development.

If I had $200 million sitting around, I would donate it to the city to make this happen.