Milwaukee a Leader in City Center Job Growth

So says a recent study. But is the data more than a passing fad?

Recently a report titled Surging City Center Job Growth was released by City Observatory, a new research center in Portland, Oregon. It looked at job growth in the 51 largest American cities. Because of incomplete census data, 10 cities were eliminated.

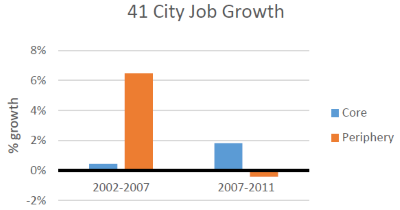

The study compared job growth in the city core (within three miles of the city center) with that in the remainder of the metropolitan area. It then compared two periods: from 2002 to 2007 and from 2007 to 2011. The first represents the run-up to the Great Recession. The second includes the recession itself plus the first two years of job recovery.

One difference between this study and previous ones, is that this study used a three-mile limit rather than political boundaries. In Milwaukee a three mile radius from Downtown would reach roughly to Lake Park on the northeast, Capitol Drive on the north, Miller Park on the west, and south to Bay View.

One major conclusion is that between the two periods there has been a major shift in the location of jobs. As can be seen in the graph to the right, in the first period jobs barely budged in the 41 cities’ core areas. Almost all the growth was in their peripheries. In the second period, the locations switched position, with all the growth taking place in the cities’ cores.

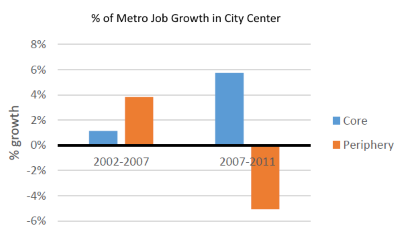

This pattern did not hold for every city. Houston, Dallas, and Los Angeles grew much more at the edges than in their cores. Milwaukee, however, did show this pattern. In fact, it showed it much more strongly than the average American city, as shown in the next graph. This is consistent with the population shifts I noted in two articles (here and here), in which Milwaukee and its close-in suburbs seemed to have reversed the decades-long pattern of shrinkage in the core and growth in distant suburbs.

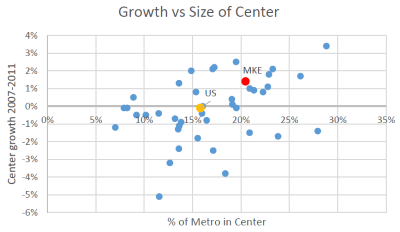

Surprisingly to many Milwaukee residents, Milwaukee is already a fairly dense city, with 20 percent of jobs within three miles of its center. This compares to about 16 percent for the average city in the study. In terms of growth of jobs in the center, that seems to lend an advantage.

The next graph plots the cities’ concentration of jobs on the horizontal axis. The further to the right they are, the higher the percentage of job growth within three miles of their center. Milwaukee, shown with a red dot, comes in at twelfth-most concentrated, just ahead of Denver. The average US city is shown with a yellow dot.

The vertical score shows the percentage growth of the city centers during the period from 2007 to 2011. Perhaps not surprisingly, cities that already have a larger concentration of jobs in the central core appear to have an advantage in attracting more jobs in that area.

This is consistent with much of the current thinking about the comparative advantage of cities: that they are attractive to people who need to interact with other people. Professionally this includes lawyers who need to be close to their clients, bankers, artists, entrepreneurs, and many others. Large corporations may have less need for cities if they have internalized these interactions.

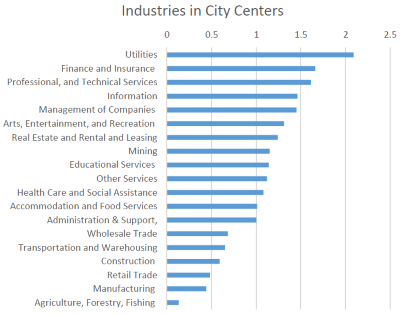

To get an idea of which industries are attracted to city centers, the report used the census data on these businesses. It calculated a quotient based on whether an industry was over or under-represented. Since on average city centers have 16 percent of jobs in a city, an industry with 16 percent of its jobs in center cities was given a “1” ranking. Industries with values over one are concentrated downtown while those with values less than one are under-represented.

Retail trade is one example of an industry that was formerly concentrated in downtowns. When I came to Milwaukee, it had three strong department stores. People used to come downtown to do their shopping. Now they go to suburban malls or order through the internet.

Manufacturing is another example. Many of the condominiums in the third Ward were carved out of former manufacturing plants, multiple-floor warehouses located on the Milwaukee River and adjacent to railroad tracks. Manufacturing in general has been hurt in recent years but more so in cities. Cheap truck transportation has largely relieved the need to be next to transportation hubs. By moving outside the city and on cheaper land, plants spread out rather than go upwards, saving the cost of reinforcing floors and heavy duty elevators to hold heavy equipment.

The report finds that industries gravitating towards city centers on average pay more than those moving towards the periphery. While this seems like good news for people living in cities like Milwaukee, the higher pay is accompanied by higher educational expectations. The downside is that this contributes to a growing geographical mismatch between where unskilled workers live and where the jobs that could use their services are located, as industries like manufacturing and construction concentrate in the periphery.

The report finds that the industries favoring city centers have been growing faster than those favoring the periphery. Again this seems like good news for cities. However, the report notes that in the past this advantage has been swamped by a disadvantage in regional competition: Even the industries over-represented in city centers were tending to move out.

The report attempts to separate the “composition” effects from the competitive effects. If the core grows faster simply because the kind of industries that tend to be located there grow faster, that is a composition effect. If the cored grows faster because it attracts more businesses, that is a competition effect. The two effects can work in the same direction or pull in opposite directions.

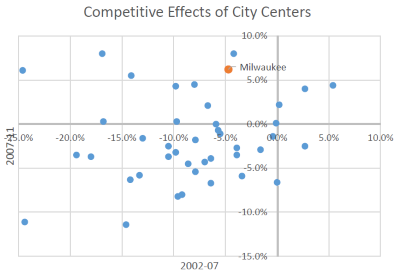

The chart on the right compares the report’s calculation of the competitive effect of city centers in the 2002 to 2007 period (on the horizontal axis) to those for 2007-2011 (on the vertical axis). It is notable that just a few city centers (to the right of 0%) had positive growth from 2002-2007. Since then a number have moved into the positive range (above the darker gray line), including Milwaukee’s, shown as a red dot.

Will the trend favoring the growth of jobs in city centers continue? There are a number of reasons to be cautious. The periods covered in this study are relatively short. What will happen as the recovery gains momentum (and may already have happened in the years since 2011 for which data has not yet been published)?

Will lower gas prices continue and make commuting long distances less burdensome? Will the problems of poverty and urban schools put a damper on the increasing popularity of urban neighborhoods—or will inner city residents find ways to benefit from increased prosperity?

There is the danger of jumping to conclusions or succumbing to wishful thinking regarding the future of our urban core. The number of years with available data is still quite scant. Calculating job changes from year to year involves taking the differences of very large numbers. A relatively small error in the job count can lead to very large errors in calculated difference.

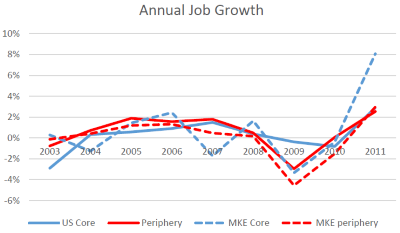

The chart to the right shows the annual change in jobs in the central core of cities (shown in blue) and in their peripheries (shown in red). Results for the average city are shown with solid lines; dashes are used for Milwaukee. The volatility of the data should make anyone pause before jumping to conclusions; the long-term trend is hardly clear-cut.

At the same time the desire for urban living is clearly on the increase. With its decision to build a streetcar, Milwaukee seems well positioned to compete for residents and employers who want to have something like San Francisco without its higher costs and pressures.

Data Wonk

-

Scott Walker’s Misleading Use of Job Data

Apr 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Apr 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Partisan Divide on Education Hurts State

Mar 27th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Mar 27th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Will Wisconsin Supreme Court Legalize Absentee Ballot Boxes?

Mar 20th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Mar 20th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

To anyone concerned about land stewardship issues, including Downer Woods and the Knowles-Nelson Stewardship Fund, here’s what an aide to Chris Larson recommends:

“Right now people who want to advocate need to contact members of the Joint Finance Committee and their own legislators. Dems, I would think, will do an amendment to remove the provision in JFC and on the floor when we get there. They should call and email.

People should also show up to the public hearings around the state if possible. Here is the list of them as far as we know – I don’t have specific times at this point:

Wednesday, March 18- Brillion High School

Friday, March 20- Alverno College in Milwaukee

Monday, March 23- UW Barron County in Rice Lake

Thursday, March 26- CAL Center in Reedsburg.”

As Barbara Notestein wrote above, there does not seem to be any need for the governor & legislature to be tinkering with the fine points of regulations that govern a specific UW campus, especially 20 acres of protected land and buildings. The potential to create a UW authority has nothing to do with this issue, since all laws affecting UW will need to be changed, if and when such an authority is formed. One possible reason for deleting these Downer Woods protection provisions is to set the stage for a stealth land sale or development project that can fly under the radar, especially before a UW Authority is created, which will not happen overnight.