Is Milwaukee the Leading Freshwater City?

Perhaps no American city provides more access to its rivers and lake shore. First of a series.

The effort to transform Milwaukee into a global hub for water technology is still in its early stages, and shows promise, but however impressive this venture, it’s arguably an outgrowth of a much longer term – and in many ways more extraordinary – series of initiatives focused on Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape going back many years. This longer term effort, focused on degraded water resources and blighted industrial lands bordering Milwaukee’s urban rivers, has revitalized Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape in ways that I believe may be unmatched by any other U.S. city. In addition, the unique geography of the city, and decisions going back a century or more to keep the lakefront relatively undeveloped, have assured that Milwaukee’s rivers and lake shore are uniquely accessible to people.

No other Great Lakes city offers as much access to its lakefront as Milwaukee. Few cities have developed as long a riverwalk as Milwaukee or features rivers that are more accessible, right-sized and less subject to flooding than Milwaukee. And Milwaukee has been ahead of most cities in improving its sewage system and cleaning up its rivers and lakeshore, and in naturalizing and removing dams on its rivers. The environmental and physical transformation of these waterfront areas has been a key component of Milwaukee’s general urban renaissance, and the continuing transformation of this extraordinary landscape over the coming decades may ultimately have a greater economic impact on the city than the current business-focused water initiative, through its ability to fundamentally transform Milwaukee’s “brand,” attract tourists and delight residents.

This series will examine the factors that makes Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape so unique, comparing this city to others across America. It’s a good news story about unique assets we tend to take for granted, but certainly shouldn’t.

Part 1 – Milwaukee’s Extraordinary Lakefront and Estuary

The Milwaukee lakefront’s most exceptional attribute may be the degree to which it is free of blighting features such as old industrial plants or vacant industrial land, active rail lines, and major highways or other restricted access roadways. Waukegan provides a nearby example of a city whose downtown has a nearly identical physiographic setting as Milwaukee, with the east edge located on a bluff overlooking the waters of Lake Michigan approximately a quarter-mile to the east. However, while Milwaukee’s downtown is bordered to the east by a continuous band of high quality public green space, recreational amenities, and buildings of exceptional architectural design, the equivalent urban space in Waukegan is occupied by a four-lane restricted access highway, six active rail lines, and a broad strip of blighted industrial land.

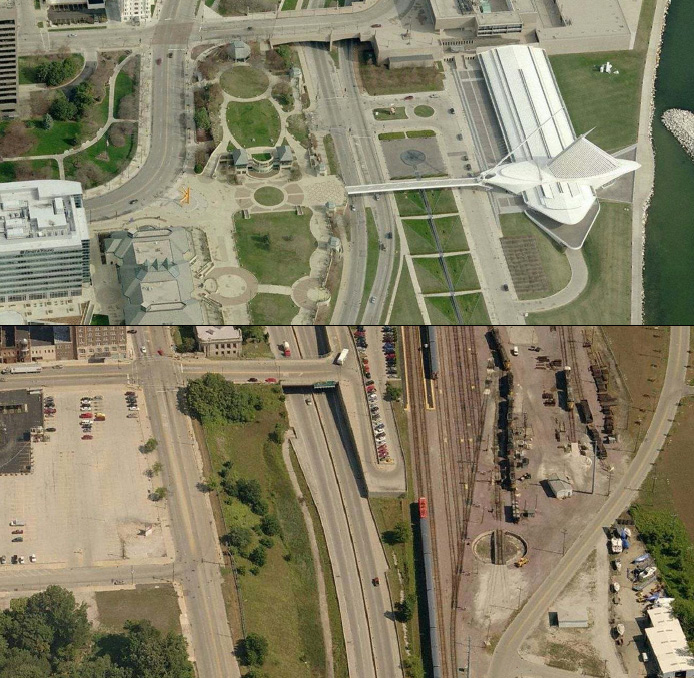

Downtown Milwaukee (above) and the equivalent geographic space in downtown Waukegan (below). Waukegan’s lakefront is dominated by a restricted access highways (planned in Milwaukee, but never built), and active rail lines (historically present, but long since removed from Milwaukee’s downtown lakefront), and active and vacant industrial land.

Chicago, with one of the most beautiful downtown settings of any city in North America, has an 8-lane restricted access highway (Lake Shore Drive) in the geographic equivalent to Milwaukee’s Lincoln Memorial Drive – cutting off the nearshore residential neighborhoods from convenient access to the lakefront. Even the edge of Chicago’s central business district on Michigan Avenue is separated in part from the lakefront parks and museums by a 200-foot wide concrete canyon/no-man’s land one block to the east that contains 4 to 6 active rail lines. Although several billion dollars of improvements such as Millennium Park have been constructed over portions of this railroad infrastructure over the past several decades, these improvements have still not fully eliminated this blighting feature from Chicago’s downtown and lakefront – a reflection of how difficult it is to eliminate this type of inconveniently located but essential transportation infrastructure once in place, and a measure of how exceptional is it for Milwaukee to have a lakefront that is now permanently free of such features.

Look at other Great Lakes cities and you’ll find a combination of one or more of these blighting urban landscape features (as well as others such as waterfront sports stadiums surrounded by acres of asphalt parking lots) which scar significant portions of the waterfronts of every other major or mid-sized city. Although Milwaukee has industrial areas on a portion of its south lakefront, these are relegated to a port area that is largely separate from the downtown and adjoining residential neighborhoods.

Milwaukee’s lakefront as it exists today has benefited in significant ways from more than a century of farsighted planning decisions – and in one key instance, a last minute reversal of decades-long plans to construct a six lane freeway (the “Downtown Loop Closure” or “Lake Freeway North”) along the east edge of the downtown. The exceptional quality of the lakefront today is also the result of the transformation of several former transportation infrastructure and industrial facilities historically located in this area. These include rail lines which extended north along the bluff, and a rail yard present in the area now occupied by the Italian Community Center. A downtown airport (Maitland Field) was transformed into one of most beautiful waterfront festival grounds in North America.

The result is a lakefront landscape that is not only beautiful but essentially unmatched in its accessibility and lack of blighting features. The further improvements underway as part of the $34 million project reconfiguring the I-794 off ramps will only add to this exceptional component of Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape.

Although some water quality challenges and periodic beach closures remain a concern for the lakefront, the continuing efforts by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, Shorewood, and other local governments to eliminate combined sewer discharges to the rivers and lake, have resulted in water quality in Milwaukee’s harbor that was clean enough for it serve as the swimming venue for the USA Triathlon National Championships for the past two years (and now scheduled to return on August 8-9, 2015 for an unprecedented third consecutive year in one city).

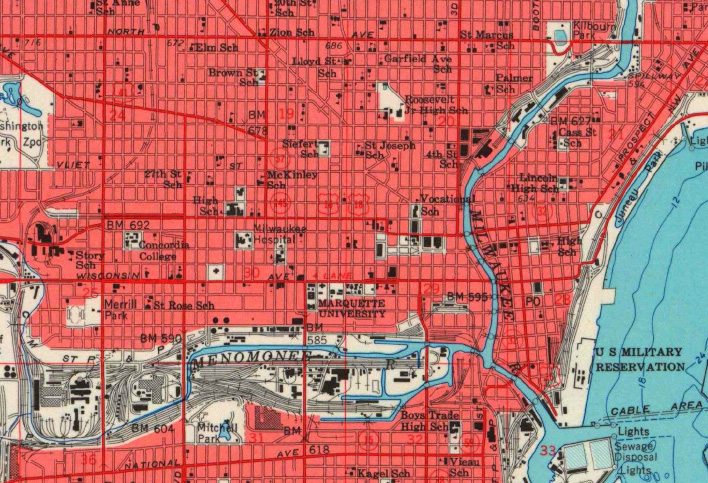

Figure 2. Current Milwaukee residents may not fully appreciate the way railroad infrastructure once dominated not only Milwaukee’s lakefront, but significant portions of the Milwaukee, Menomonee, and Kinnickinnic Rivers, as shown on this topographic map dated 1958. Although some of this transportation infrastructure has been replaced by highways, the locations have generally shifted away from the lake and river shorelines. (Courtesy of U.S. Geological Survey).

Milwaukee’s Estuary

The second extraordinary component of Milwaukee’s freshwater landscape is the interconnected freshwater estuary formed by the lower reaches of its three urban rivers. Milwaukee’s estuary is an extraordinary urban water and landscape feature that is perhaps unmatched by any other major U.S. city in its accessibility, high quality urban setting, and low susceptibility to future water related catastrophes and flooding and ebbing.

Long-time residents accustomed to viewing the downtown portion of the Milwaukee River may not fully appreciate how unusual it is for major office buildings to be constructed directly adjacent to a large river. In terms of urban riverfronts, this is really something quite extraordinary, and is attributable in large part to water levels in the estuary that are relatively stable and approximately equal to that of Lake Michigan.

Although Lake Michigan’s water level has been in the news in recent years as a result of the historic low level achieved in early 2013, the approximate 7-foot total variation in Lake Michigan’s water level over the past 150 years is relatively small in the context of variations in the water levels of other major urban rivers. For example, in June 2013, the Mississippi River at St. Louis reached a level that was 45 feet higher than the low recorded that January. The water level rose by 19 feet within a period of 8 days. As a consequence of the enormous annual variations in its water level, the Mississippi River at St. Louis has a profoundly different character and relationship with downtown St. Louis than the Milwaukee, Kinnickinnic and Menomonee Rivers have with downtown Milwaukee – a relationship that in St. Louis is characterized by the presence of massive flood control structures to address the permanent potential threat of catastrophic flooding.

Annual variations in water levels of up to 50 feet have occurred in other US rivers, including the Missouri and Ohio Rivers. Periods of low water present a separate problem for St. Louis and other cities, as the margins of their rivers periodically transform during summer months into malodorous and unsightly mudflats strewn with debris.

Similarly, the major waterfront cities on America’s Pacific and Atlantic coasts are subject to tidal variations on a daily basis, and to destructive storm surges on a rare, but increasingly frequent basis, most notably, the 13-foot storm surge that inundated large areas of New York and New Jersey’s waterfronts during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Remarkably, the flood levels achieved during Sandy do not represent worst case conditions, as the maximum potential storm surges based on modeling conducted by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (i.e., for category 4 or 5 hurricanes hitting during high tide) are calculated to be approximately 38 feet in New Bedford, Massachusetts, 33 feet in Corpus Christi, Texas and in New York City (near the JFK Airport), 30 feet in Boston, 28 feet in Tampa, and 27 feet in Charleston. Regardless of the probability for a worst case storm surge event occurring at any of these waterfront cities during the next several decades, the threat of future catastrophe shapes the fundamental character of their waterfronts, and the location and types of amenities that can be constructed, financed, or insured.

Although other major cities on the Great Lakes, such as Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and Buffalo, have urban rivers that form similar estuaries with Lake Michigan or Lake Erie, none of these cities have revitalized their urban rivers to the degree that has occurred in Milwaukee (a topic that will be explored in more detail in a future story). In conclusion, Milwaukee’s estuary, with nearly 10 miles of water channels passing through the heart of the downtown and the revitalized Third Ward, Fifth Ward, and Menomonee Valley neighborhoods, represents a second freshwater landscape feature of Milwaukee that is extraordinary in both a regional and national context.

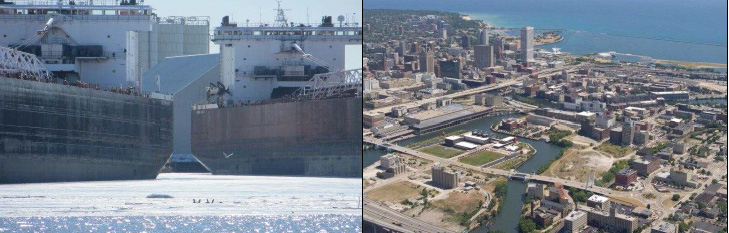

Figure 3. “Boats” on the lower portion of the Kinnickinnic River (an example of the type of authentic waterfront feature not likely to be seen on San Antonio’s Riverwalk).

Figure 4. The Harley Davidson Museum, the former Pfister and Vogel Tannery complex, and the former Reed Street Yards are among urban development sites taking advantage of the exceptional freshwater landscape within the Milwaukee Estuary.

David Holmes is a Milwaukee-based environmental scientist and urban revitalization consultant. He is also a coauthor of a book on the history of Milwaukee’s Chinese community (Chinese Milwaukee).Next in our Series: How Milwaukee Improved Its Urban Rivers

Freshwater Mecca

-

Milwaukee’s Extraordinary Freshwater Future

Feb 20th, 2015 by David Holmes

Feb 20th, 2015 by David Holmes

-

Milwaukee Leads Great Lakes Cities

Feb 13th, 2015 by David Holmes

Feb 13th, 2015 by David Holmes

-

Milwaukee’s Riverwalk Vs. San Antonio’s

Feb 4th, 2015 by David Holmes

Feb 4th, 2015 by David Holmes

The main point of the article is sound: Milwaukee does have great access to its waterfront. Several good decisions across decades got it there.

But don’t let present-day cloud an important understanding of how the city developed. Without those “inconvenient” rail lines, this city might not even be here or be what it is. And aside from the people who live within a mile of the lake, the rest of the population will need at least one or more of those “inconvenient” transportation items (rail, sea of parking, freeways, etc) in order to come enjoy the lakefront.

What a well-researched, informative look at our exceptional lake and estuary resources! We often do take our pristine lakefront for granted, and our now-accessible downtown riverfront. They are crucial to quality of life for residents and as appealing features for tourists, including our rare miles-long stretch of lakefront public parks.

And thanks are due to attorney Charlie Kamps (and others) who spent years fighting that decades-long plan to build a blighting six-lane freeway along the lakefront. He’s still advocating for adherence to the state constitution’s public trust doctrine as it relates to filled lakebed.

We’re all lucky that far-sighted folks worked to create these legacies, and that parks advocates (sometime chastised for being “inflexible”) have ensured that our extraordinary public landscapes have been preserved. They increase all nearby property values (and thus tax coffers) and the area’s overall economic climate. Continuing that conscientious stewardship will contribute mightily to sustaining Milwaukee’s long-term vitality and well-deserved bragging rights as a leading freshwater city.

Brilliant! Keep it coming.

Great article! Thanks for highlighting our waters and how important they are to our City and economic vitality!

Dave, Wonderful observations. I guess MIlwaukee has more gonig for it than I would have thought. A real future? Growing up here in the 60’s all I wanted to do was leave.

A hopeful article! As a birder (did you know there are more birders now than golfers?), I’d like to see future articles in this series identify good birding locations and/or festivals. As you know, birders bring in millions of tourist $$$. Other locations around the Great Lakes are cashing in. Why not Milwaukee?

Keep the info coming. I use it for my Historic Milwaukee Inc. tours