The Democratic Disadvantage

Republicans can continue to control the legislature with 46% of the statewide vote. How can Democrats overcome this edge?

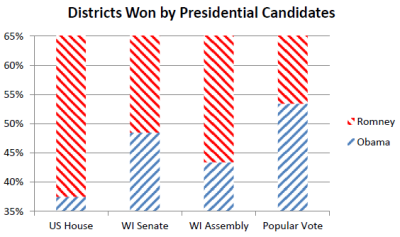

In the 2012 presidential election, Barack Obama won the popular vote in Wisconsin by seven percentage points. If the vote had been allocated by legislative district, however, he would have lost. As can be seen in the table below, he lost a majority of US House districts, of state senate districts, and of assembly districts. In fact, he won only 43 of the 99 assembly districts. (These calculations are based on spreadsheet published on the Wisconsin Government Accountability Board website.)

If Wisconsin’s electoral votes were allocated by congressional district, Obama would have won five electoral votes in Wisconsin instead of all ten.

These numbers give some measure of the Republican advantage built into legislative districts in Wisconsin. Part of this advantage resulted from the deliberate strategy of placing as many Democrats as possible in a few districts, aided by the heavy concentration of Democrats in cities.

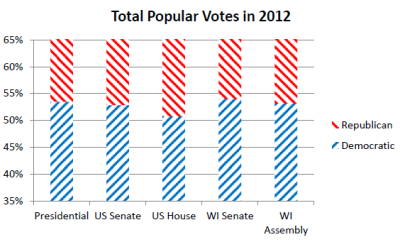

Despite losing control of both houses of the legislature in 2012, the recorded popular vote totals favored Democrats. A simple tabulation of votes state-wide shows a Democratic majority in every case.

Simply adding up total votes, however, probably overstates the Democratic advantage in public sentiment. Democratic candidates were missing in four assembly races while Republicans missed a whopping twenty three. Pretty obviously, a party with no candidate receives few votes. But one-sided districts also likely depress the vote total for the winning party, if its supporters saw little reason to vote when their candidate was assured of success. Evidence for this conjecture is that the average vote total for uncontested assembly seats was just under 21,000, compared to 29,000 for contested seats.

Even with both parties on the ballot, vote totals may be depressed if one candidate is regarded as a shoe-in. Political parties and outside groups concentrate their resources on the handful of competitive races. In addition, the strongest potential candidates may be reluctant to enter races where the chance of success is remote. This effect can be seen in the US House races, all of which had candidates from both parties. The largest gaps between the presidential and house votes occurred in the 4th and 5th districts, the most heavily Democratic and Republican, respectively.

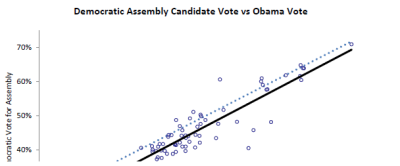

To estimate voter sentiment in the state senate and assembly districts, while avoiding the distortions caused by noncompetitive districts, I started with the presidential vote in districts with two legislative candidates. The chart below compares the percentage vote for Obama (on the horizontal axis) to the percentage vote for the Democratic Assembly candidate (ignoring write-ins and third-party votes).The solid black line shows the best fit.

On average, Democratic legislative candidates underperformed Obama. The dotted line shows where the fit would be if they had performed as well as Obama. In the Assembly six Republicans won districts that Obama won, while only two Democrats won districts carried by Romney.

Applying the linear regression relationship to all districts, Obama’s state-wide 53.5 percent vote translates to an average Democratic assembly candidate advantage of only 50.5 percent. These results suggest majority support for Democratic candidates in the election, but far short of the super-majority needed to take control of the legislature.

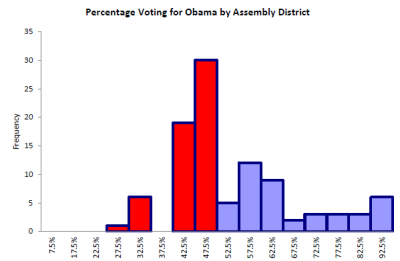

The basic strategy behind using redistricting for partisan advantage is to concentrate the other party’s voters in a few highly partisan districts. This allows the creation of a larger number of seats with a safe—if lower—majority of voters supporting the party controlling the redistricting. The chart below shows how this strategy played out in the Wisconsin Assembly. Districts on the right of the plot (colored blue) were won by Obama, usually by very large margins; those on the left (in red) by Romney, usually by much smaller margins. A plot of Senate districts shows much the same pattern.

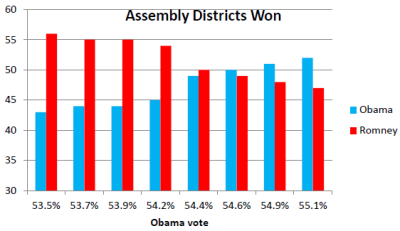

What would it have taken for Obama to have won a majority of seats? Obama won 53.5 percent of the popular vote and lost 56 of the 99 Assembly districts. The chart below shows the number of districts he would have won if his margin increased, assuming the same percentages of Republican votes switched in every district. As can be seen the tipping point comes around 54.5 percent, about 1 percent higher than Obama actually won. For the Senate, the tipping point comes just over 54 percent; for the US House it is around 55.5 percent.

Although individual races depend partly on the strengths and weaknesses of the individual candidates, this means a generic Democratic candidate needs to attract about 55 percent of Wisconsin voters if Democrats are to win the state legislature. Put another way, Republicans can control the legislature so long as they win at least 46 percent of Wisconsin voters.

What does this mean for the upcoming elections this November? As Steven Walters reports based on a review of nomination papers, there will be a large number of districts decided in the primary.

Another way to assess the Democratic challenge is to look at individual districts. In the Assembly, Republicans have a 21 vote majority, so that Democrats winning control would require a switch of 11 seats. This seems like an insurmountable challenge, particularly since only six Republicans represent districts were won by Obama.

The state senate looks more promising for Democrats. There, the Republicans enjoy only a three vote majority so that a net switch of two seats would give control to the Democrats. And two districts with Republican incumbents were won by Obama. Furthermore, the Tea Party has helped put these seats in play by helping convince the incumbents—Dale Schultz and Mike Ellis—not to run again. Unfortunately for the Democrats the district represented by Democrat John Lehman was won handily by Romney. Perhaps bowing to the inevitable, Lehman is running for Lieutenant Governor. Thus, using the Obama vote, Democrats stand to gain a net of one seat, still short of winning control.

Compared to Democrats, Republicans seem to be sitting pretty. Thanks to redistricting they can maintain control of the legislature even as a minority party. But they face long-term dangers.

For most GOP legislators there is little incentive to search for common ground across parties. In fact the political incentives are in the opposite direction, to downplay cooperation for fear of being accused of being a “RINO” (Republican in name only) and being targeted by groups intent on purging those considered insufficiently conservative. Thus, the growth of safe seats further encourages the party’s ongoing move to the right. Like an industry that is protected by tariffs and loses its competitive edge, the Republican Party is in danger of taking advantage of its protections to become less relevant.

Republicans may find it increasingly difficult to find candidates for state-wide office—who have experience in attracting independents and Democrats. It’s hard to imagine a candidate with the cross-over appeal of Tommy Thompson emerging from the present legislature. Even Scott Walker, despite his very partisan reputation today, won three elections in heavily Democratic Milwaukee County before running for governor. If nothing else, this experience may have given him a sense of what not to say when he ran for governor.

The intensity of Republican efforts to tilt the playing field in their favor suggests an underlying pessimism about the party’s long-term future, based on demographic and other trends. While both parties have tried to use redistricting in their favor in the past, the time and money devoted to redrawing boundaries after the 2010 census was something new. When combined with many other efforts to gain advantage, including voter ID requirements and restrictions on early voting, it suggests the Republican Party believes it needs a tilted playing field to win.

For Democrats the challenge is how to reconcile two pressures that push them in opposite directions: (1) to have a chance of winning control of the legislature, they need to broaden their appeal, but (2) as legislators in heavily Democratic districts they need to guard against primary challenges. I will look at each of these in turn:

1. Without attracting a super-majority of 55 percent of voters, under the current district map Democrats are doomed to minority status for at least the next eight years. As noted, 55 percent is a higher margin than Obama received in the 2012 election, and and even higher than for the average Democratic legislative candidate. Adding to the challenge, the Democratic vote total normally drops more than the Republican total in midterm elections. Combined with other measures passed to discourage voting by Democratic constituencies, Democrats face serious barriers to winning control.

This would suggest Democrats must pursue a big-tent strategy by reaching out to voters with a variety of viewpoints. Such a strategy would depend on recruiting compelling candidates and giving them the freedom to tailor a message to their district. But this runs up against current trends in favor of party discipline in the legislature, making it harder for a Democratic candidate to tailor a message to the district.

2. The imperative for most Democratic legislators as individuals is the opposite of what is needed for a big tent strategy. Their very partisan districts mean they are far more vulnerable to a primary challenge than defeat by a Republican. Thus the individual incentive is to become more partisan rather than winning over independents or moderate Republicans.

In the Milwaukee area, an organization called DemTEAM has taken a leaf from the Tea Party and the Club for Growth, by recruiting candidates to run against Democratic incumbents it considers insufficiently loyal to its agenda. It has had some success in removing legislators whose views on education do not align with those of the teachers’ unions. Since all the legislators targeted came from safely Democratic districts, it has not directly cost any Democratic seats, unlike the impact of the Tea Party. But it seems hard to believe that a party which would not welcome Barack Obama’s or Corey Booker’s views on education would be in a strong position to win over additional voters.

The counter-argument made by Tea Party supporters on the right and Tea Party-like efforts on the left is that allowing a diversity of views will sap enthusiasm, focus, and turnout. In the end, however, one’s judgments of these strategies may depend more on one’s belief as to whether they are good for the country than on whether they may win or lose elections.

Both parties face a strategic challenge. Do they attempt to win by stressing ideological homogeneity and therefore create more enthusiasm in their base? Or do they attempt to broaden their base, by being a comfortable place for people of varying viewpoints? Just looking at the numerical disadvantage it suffers, the party most likely to benefit from base-broadening in Wisconsin is the Democratic Party. The question is whether its internal dynamics will allow it to do so.

Data Wonk

-

Scott Walker’s Misleading Use of Job Data

Apr 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Apr 3rd, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

How Partisan Divide on Education Hurts State

Mar 27th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Mar 27th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

-

Will Wisconsin Supreme Court Legalize Absentee Ballot Boxes?

Mar 20th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

Mar 20th, 2024 by Bruce Thompson

John Lehman’s situation is a perfect example of the Republican gerrymandering at work. Before the redistricting the two Racine-Kenosha area senate districts were centered around Racine County (the 21st, almost evenly divided) and Kenosha County (the 22nd, predominantly Democratic but not overwhelmingly so). Lehman was elected in the old 21st in a successful recall of a Walker rubberstamp Republican who had unseated him in 2010.

The new map ignored county lines. The new 22nd is centered around the city of Kenosha, with just enough territory to link it to Racine, and most of that city. It’s as Democratic as central Madison.

The new 21st is designed to elect a Republican by a comfortable margin, containing most of Racine and Kenosha counties outside those cities, with just enough of the city of Racine to bring the population up to the necessary level. No wonder Lehman won’t run for re-election.

By the way, Assembly districts within the two Senate districts were also redrawn. For many years, Assembly seats 61-66 were held by four Democrats and two Republicans. Now it’s four Republicans and two Democrats.